Dynamic Scoring Confirms: House or Senate Tax Bills Would Still Add to Debt

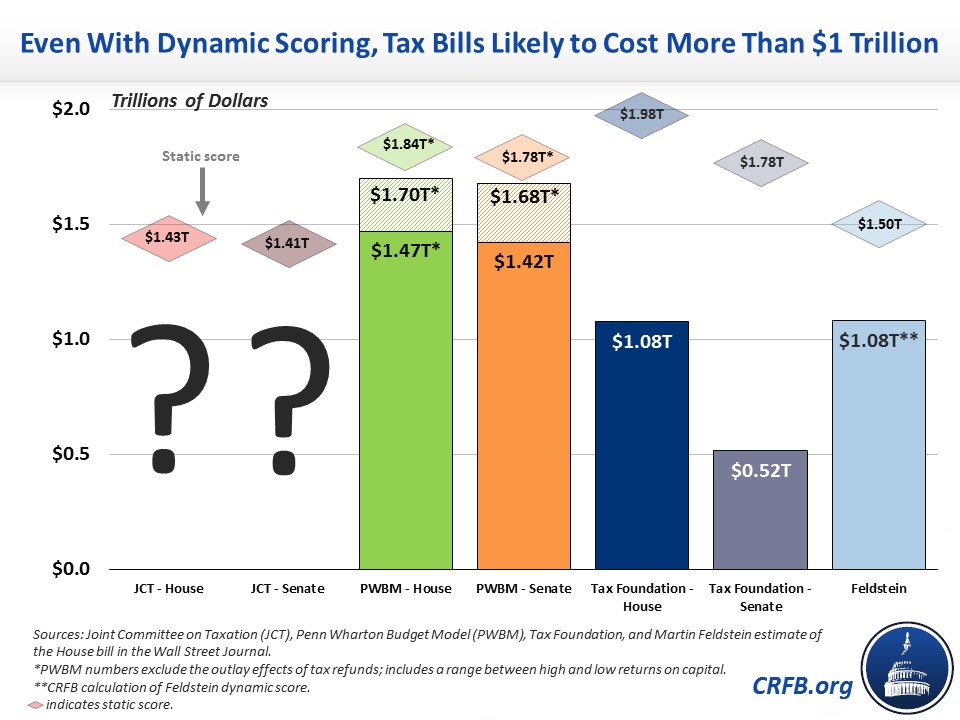

As more dynamic estimates of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) are released, they all confirm that tax cuts do not pay for themselves. Because both the House and Senate versions of the TCJA add to the national debt, they will only improve economic growth very modestly over the long term – less than they would have if they were completely paid for.

Most recently, the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) estimated the growth effects of the Senate tax bill. PWBM found that the Senate bill (as introduced) would increase the annual average growth rate by between 0.03 and 0.08 percentage points over a decade, generating between $104 billion and $359 billion of dynamic revenue. However, because the resulting faster growth would increase federal spending on interest on the debt and on programs connected to inflation, the additional economic effects would reduce the ten-year debt impact of the bill by between $27 billion and $171 billion.

The House-passed bill has similar growth effects. PWBM estimates it would generate between $143 billion and $370 billion of dynamic revenue while increasing growth by between 0.04 and 0.09 percentage points.

Based on PWBM's estimates, the Senate tax plan would still add upwards of $1.9 trillion or more to the debt, even before accounting for the many false expirations and gimmicks contained within the most recent version.

No estimates to date find that tax reform will pay for itself with growth. At most, the Senate and House bills would spur enough economic growth to offset 8 percent and 6 percent of their debt impacts, respectively. On the more pessimistic end, economic growth would offset just 1 percent of the Senate bill's debt impact, while the House bill's debt impact would slightly worsen.

Other higher dynamic estimates of the Senate and House bills from the Tax Foundation – which ignore the economic cost of higher debt – still show that both bills would add significantly to deficits despite their economic growth effects. And a rough estimate of the House bill from former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Martin Feldstein also implies significant new debt.

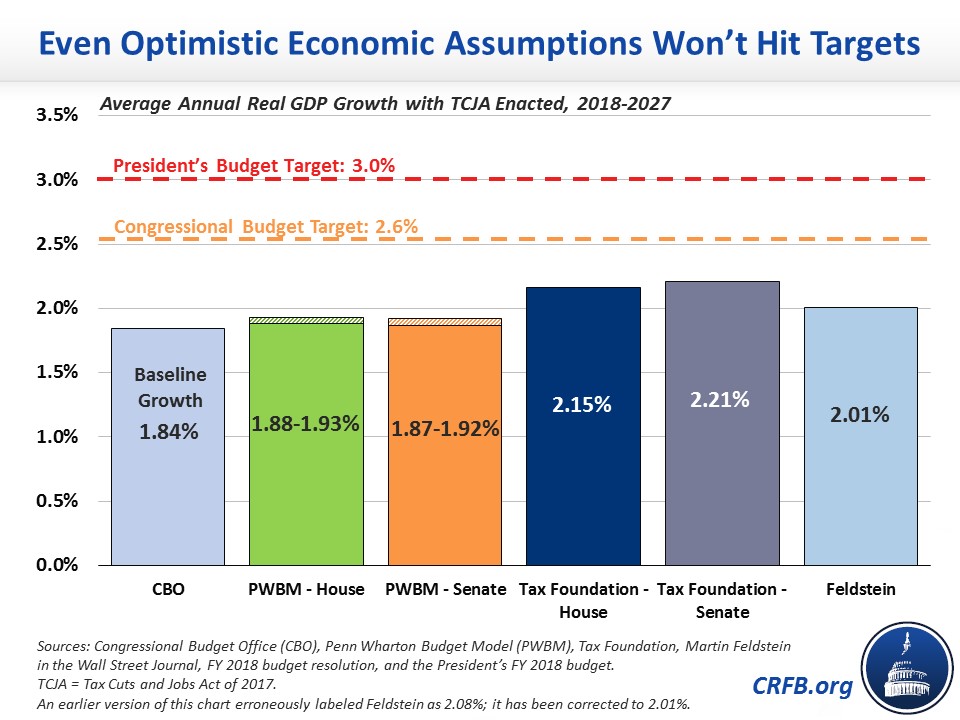

There has yet to emerge a study that suggests any version can increase economic growth by the 0.4 percentage points per year claimed to offset the plan's cost by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), let alone lift the annual growth rate to 2.6 percent as assumed in the budget resolution or 3 percent as assumed in the President's budget. The Tax Foundation study comes close – increasing growth by an average of 0.37 percentage points annually – but that estimate is based on a previous version of the Senate bill, which now contains many arbitrary sunsets that will likely undermine the Tax Foundation's long-run growth estimates. As the Tax Foundation explains, the growth effects will taper off as the expiration dates near.

Based on PWBM's estimates, tax reform might boost the real GDP growth rate to 1.9 percent over the next decade. Even under estimates from Feldstein and the Tax Foundation – both of which ignore the negative effect of higher debt – economic growth would remain between 2.0 and 2.2 percent.

Estimates that show large growth effects generally look at the positive impact of lower marginal tax rates without considering the negative impact of rising debt, and even those estimates show these tax bills do not pay for themselves through growth. Indeed, the Tax Foundation effectively assumes an unlimited supply of savings so that any increase in debt is fully offset by increases in domestic savings and foreign investment. The PWBM and Congressional Budget Office (CBO) models also assume rising debt leads to higher domestic savings and foreign investment, but a portion of the higher debt comes at the expense of ("crowds out') private investment. For instance, CBO believes every $1 in additional deficits crowds out $0.33 in private investment. Evidence suggests the PWBM and CBO models paint a more accurate picture of the economy, and even the Tax Foundation admits some crowd out of investment would occur as deficits rise.

Importantly, the negative effects of debt grow over time. Under the PWBM model, the Senate bill actually hurts GDP growth after 2027 – it estimates a 0.02 to 0.04 percentage point reduction in average growth between 2028 and 2040. As a result, PWBM estimates the economy will be somewhere between 0.5 percent larger and 0.2 percent smaller in 2040 under the Senate tax bill as compared to current law. The PWBM estimate of the House bill tells a similar story, with the economy being either no larger or up to 0.8 percent larger in 2040 under the House bill.

PWBM's results confirm the findings from many previous studies: a tax bill financed by adding more to the already unsustainable national debt will actually have slower growth than one that does not add to the debt. Tax cuts do not pay for themselves, even after assuming higher economic growth as a result of them. Adding $1.5 trillion to our already unsustainable national debt path is a step in the wrong direction. In order to reduce the bill's cost, lawmakers should either scale back the bill's tax cuts, add more base broadening, or identify other offsets to make it more fiscally responsible.