A Closer Look at Refundable Tax Credits

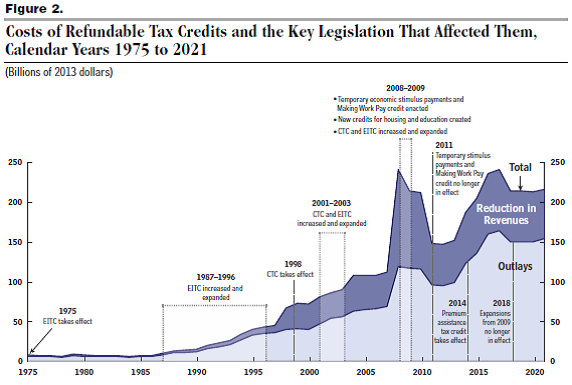

Yesterday, CBO issued a report on refundable tax credits, examining many issues involved with the credits. The first refundable credit, the Earned Income Tax Credit, was created in 1975 to offset the payroll tax for low-income people. The number of refundable credits has increased to a high of 11 different credits in 2010, and 5 currently. The cost of these tax expenditures has also risen, reaching a high of $238 billion (in 2013 dollars) in 2008 due to many economic stimulus measures before falling to $150 billion this year. The cost of credits will rise again as new health insurance credits kick in, bringing the total to $213 billion (in 2013 dollars) in 2021.

Tax credits are typically more progressive than deductions, since the value to taxpayers is not dependent on their marginal tax rate. Refundable credits are even more progressive than nonrefundable credits because they allow people to benefit in full even if they have no tax liability.

The current refundable credits serve a variety of functions. Both the EITC and the Child Tax Credit are earnings based credit which vary with the number of dependents, although the credits apply to different income ranges (the CTC is available at higher incomes than the EITC). The American Opportunity Tax Credit is designed to promote higher eduction by giving a tax benefit for spending on college tuition. A few credits come from the Affordable Care Act -- the small business health care tax credit and premium assistance tax credit -- as centerpieces to its coverage expansion. Other refundable tax credits, such as the Making Work Pay tax credit and the first-time homebuyer credit, were temporary stimulus measures which expired.

Source: CBO

Compared to direct spending programs, these tax credits have advantages and disadvantages. The lag between the subsidized action taking place and filing a tax return can reduce the effectiveness of credits, but they tend to reach more beneficiaries due to their being less of a burden for claiming the benefit. In terms of administration, credits tend to have higher error rates but require lower administrative costs.

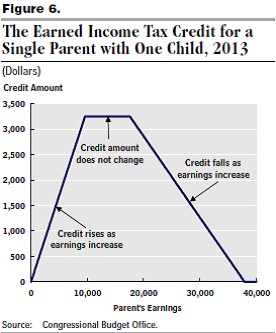

Of course, another important aspect of refundable credits is their effectiveness in achieving their specific policy objectives. For example, CBO mentions that the EITC has been shown to effectively encourage work (particularly among single mothers), but also may prove to be somewhat of a work disincentive in the income range where the credit phases out.

A few bipartisan plans have used credits as part of tax reform. The Domenici-Rivlin tax reform plan replaces the mortgage interest and charitable deductions with 15 percent refundable credits (with a $25,000 ceiling on the mortgage interest credit). Also, the tax plan combines the existing EITC and child tax credits (along with other family benefits), replacing them with a flat per child tax credit of $1,600 per child (up from the current $1,000) and a refundable credit that would be similar in structure to Making Work Pay but similar in size to the EITC. The Simpson-Bowles plan relies on non-refundable credits, converting the current mortgage interest and charitable contribution deductions into 12 percent non-refundable credits (with the value of a mortgage capped at $500,000).

Not all tax expenditures are bad policy, but it's clear that the overall complication and inefficiency of our tax code will require lawmakers to closely examine these provisions. Some tax expenditures could be eliminated while others could be reformed or consolidated, as the tax reform plans mentioned above do. Given that lawmakers will need to raise more revenue, taking up tax reform would be a great way to do it.

Click here to read the CBO report.