The Budgetary Effect of Credit Programs

Credit programs involving loans and loan guarantees are accounted for differently than most other programs in the federal budget. Whereas other programs record outlays and revenue as cash goes out and comes in, the cost of credit programs are calculated by recording the lifetime cost of the loan/guarantee in the year it is originated. However, a new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) raises questions as to whether we are measuring these programs appropriately. Under the current accounting method, certain student loans, the Export-Import Bank, and Federal Housing Administration mortgage guarantees save a combined $217 billion over the next ten years. But CBO shows that under an alternative and potentially more accurate method, these programs would cost $120 billion.

These two methods are known as Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA) accounting, which most programs use, and fair-value accounting, which is used by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and a few others. In determining the budgetary effect of credit programs, the scoring agency compares the present value of the gross cost of the loan/guarantee with expected repayments. Both methods account for the risk of participants defaulting on loans or requiring that guarantees be paid out. Where they differ is on the discount rate that is used to convert nominal dollar totals to present value. Currently, the discount rate is determined by the rate on a U.S. Treasury security with a similar maturity as the loan.

By contrast, fair-value accounting includes an added risk premium to reflect changes in overall market conditions. As CBO describes:

Market risk is the component of financial risk that remains even after investors have diversified their portfolios as much as possible; it arises from shifts in macroeconomic conditions, such as productivity and employment, and from changes in expectations about future macroeconomic conditions. The government is exposed to market risk when the economy is weak because borrowers default on their debt obligations more frequently and recoveries from borrowers are lower.

In other words, both approaches account for the risk of default given the same macroeconomic conditions, but fair-value accounting also accounts for risk exposure from changes in those conditions. By applying this risk premium, fair-value accounting more heavily discounts future year effects, making repayments worth less than under the FCRA approach.

Fair-value accounting was part of the recommendations of the Peterson-Pew Commission on Budget Reform, and according to the CBO report, it would "more fully account for the cost of the risk the government takes on." Critics of the approach argue that charging the federal government based on what private sector lenders would charge would artificially inflate the cost of those programs, since the private sector's risk aversion is not relevant for the government, and the method would put credit programs at a disadvantage relative to other programs.

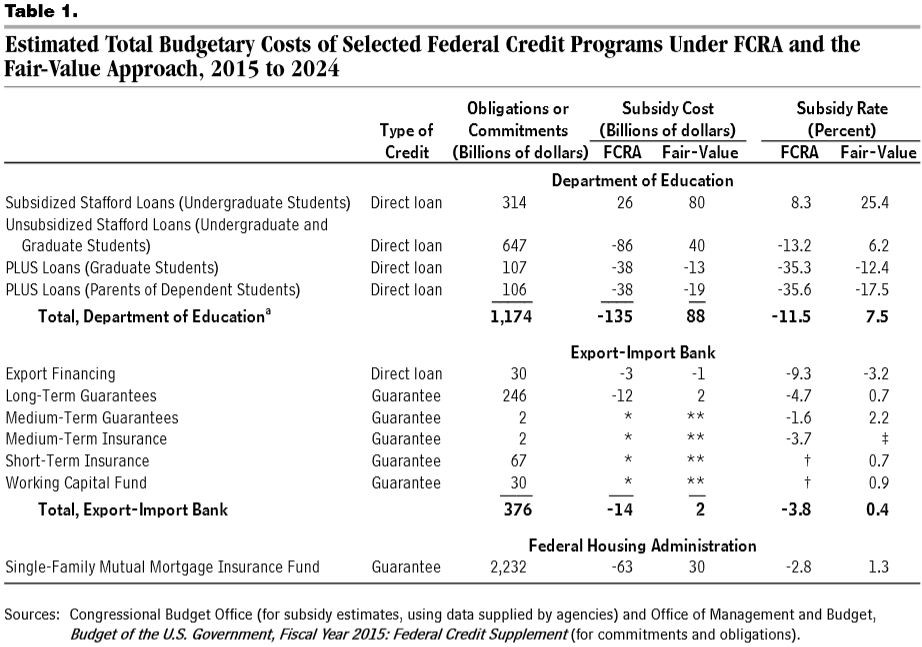

In its report, which builds on work it did two years ago, CBO estimates how certain credit programs look under current accounting rules and how they would look under a fair-value system. It evaluates Stafford and PLUS student loans, the Export-Import Bank, and mortgage guarantees from the Federal Housing Administration. Under the current rules (FCRA), all of these programs appear to make the government a profit, but they all become costs when one uses fair-value accounting.

Student loans currently show a $135 billion profit and a -11.5 percent subsidy rate (11.5 percent of the value of a student loan will become profit for the government). However, under fair-value accounting, these loans would cost $88 billion with a 7.5 percent subsidy rate (The government is expecting to lose 7.5 percent of the value of every loan offered). Ex-Im loans and guarantees go from a $14 billion profit to a $2 billion cost with a 4 percentage point swing in the subsidy rate. Finally, FHA mortgage guarantees go from a $63 billion profit to a $30 billion cost, also with a 4 percentage point swing in the subsidy rate.

The debate over which accounting method is more accurate is an important one for the federal budget. Using fair-value accounting, which many people think is more accurate, shows that programs previously considered net savings for the federal government are in fact costs or, at the very least, save much less. However, the fair-value approach is not without its critics. Deciding which standard is used will be critical for putting credit programs on a level playing field with other spending programs. Lawmakers should design a program based on how it can work best rather than its budgetary treatment.