Better Targeting in Reconciliation

As lawmakers negotiate the details of their reconciliation package, they will need to scale back some of their ambitions to prevent arbitrary policy expirations and ensure the legislation is fully (or even mostly) paid for. In some cases, reducing gross spending and tax cuts in the reconciliation package will require removing some policies from the package. But in others, policies currently under consideration could be scaled back and better targeted.

As the Washington Post editorial board recently cautioned, providing new benefits to high earners is often a poor use of limited resources. Instead, lawmakers could consider means-testing or better targeting some of their proposals. Below, we discuss a few instances where such targeting could occur.

Universal Pre-K: President Biden has proposed providing funding to states to implement universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds at an estimated cost of $165 billion. Since the proposal is universal, it would extend to households who can already easily afford pre-K and are currently paying for it out of pocket. While expanding access to pre-K has been shown to improve income potential and grow the economy, a universal program is unlikely to substantially boost pre-K enrollment among wealthier families. For that reason, the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) has estimated that while a means-tested pre-K would boost output even accounting for the economic cost of borrowing, universal pre-K would have little effect on economic growth. As an alternative to phasing out the benefit by income, policymakers could reimburse states and school districts based on a formula that accounts for the income of their population (similar to current federal public school funding).

Paid Leave: The House Ways and Means Committee mark-up proposes to provide 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave using a progressive formula that offers the highest benefit to the highest earners but the highest replacement rate to the lowest earners. The full formula, in the table below, would replace 85 percent of earnings at less than $15,080 per year, 55 percent at $34,248 to $72,000, and 5 percent of earnings between $100,000 and $250,000. In dollar terms, the benefit would rise with income from $2,988 per month for a $50,000 earner to $4,580 per month for a $100,000 earner and $5,205 per month for the $250,000 earner. That maximum $5,205 per month benefit is 30 percent higher than the maximum benefit for paid leave in the Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act and nearly two-thirds higher than the maximum Social Security benefit of $3,148 available at the normal retirement age. Lawmakers could reduce costs and better target benefits by adjusting the formula to limit how much the benefit grows with income. They could go even further and phase down or phase out the benefit for very high earners, who mostly already have access to paid leave through their employer. Alternatively, they could consider a flat benefit or cap the benefit at a much lower level.

Parameters for Paid Leave in Ways and Means Mark-Up

| Annual Income | Marginal Replacement Rate | Average Replacement Rate* | Average Monthly Benefit* |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0-$15,080 | 85% | 85% | $534 |

| $15,080-$34,248 | 75% | 81% | $1,667 |

| $34,248-$72,000 | 55% | 71% | $3,131 |

| $72,000-$100,000 | 25% | 60% | $4,288 |

| $100,000-$250,000 | 5% | 34% | $4,892 |

| $250,000+ | 0% | 25% | $5,205 |

| Memo: FAMILY Act Benefit at $250k of wages | N/A' | 19%^ | $4,000 |

| Memo: Social Security Benefit at $250k of wages | N/A' | 14%^ | $3,148 |

Source: House Ways and Means Committee

*Average means the mid-point of each range and $250,000 for the $250,000+ range

'No additional benefits accrue at or above $250,000 of income.

Expanded Medicare Benefits: The Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce markups would expand Medicare to include vision, hearing, and dental benefits starting in 2022, 2023, and 2028, respectively. This expansion would cover higher-income seniors who mostly already have access to these services through Medicare Advantage, wrap-around coverage, employer benefits, or by self-insuring against these costs. Already, the federal government spends nearly $6 per senior for every $1 spent per child, and seniors tend to be financially better off than other cohorts. Given the precarious financial state of the Medicare program, lawmakers really should shore up the program's current finances before adding new benefits. Assuming policymakers want to include these benefit expansions in reconciliation, however, there are a number of ways policymakers could better target this benefit. This could include means-testing the benefit itself, income-relating premiums for the benefit, combining a modest universal benefit with cost-sharing subsidies based on income, or fully integrating the new benefits into Medicare Part B — which already has an income-related premium that could be further strengthened as an offset.

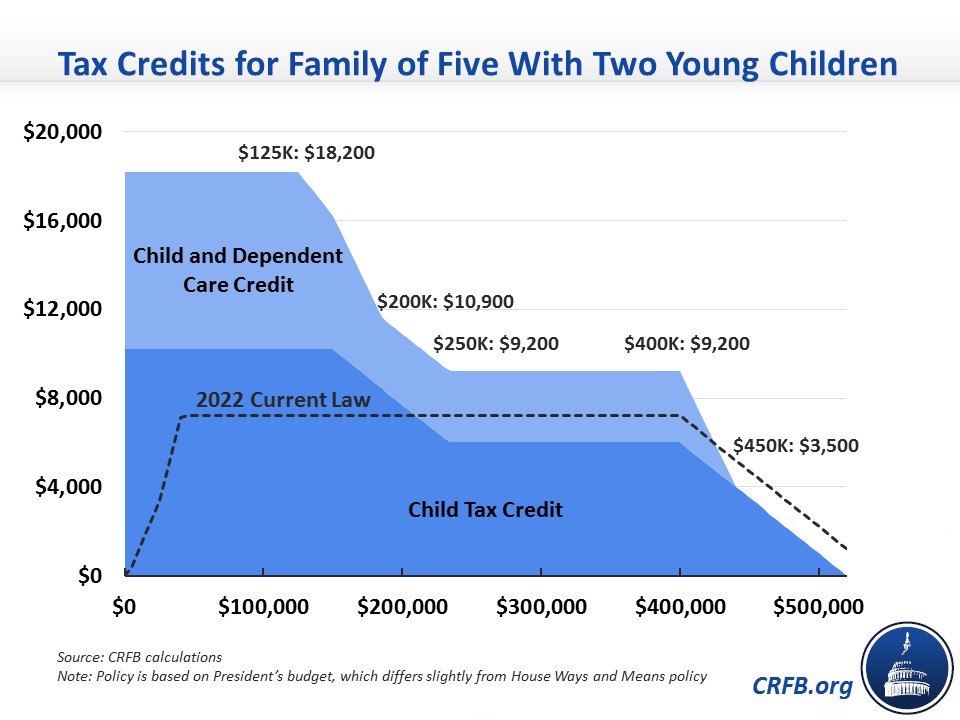

Child and Child Care Credits: The American Rescue Plan (ARP) significantly expanded the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) for 2021 by increasing the credit amounts and making them fully refundable. President Biden has proposed extending these policies, which pay families up to $3,000 per child ($3,600 per young child) through the CTC and up to $4,000 per child (with a $8,000 maximum) through the child care tax credit (Note: Ways & Means has a different proposal). While both of these credits phase out by income (and ARP actually added a phaseout to the CDCTC), they still offer relatively robust benefits for upper-middle class families. A married family of five making $125,000 per year or less can collect up to $18,200 in annual credits (assuming two kids are under age six and receiving child care). With $250,000 of annual income, that family would still be able to collect $9,200: $6,000 from the CTC and $3,200 from the CDCTC. The credits would not phase out completely until family income hit $438,000 for the CDCTC and $520,000 for the CTC.1 Lawmakers could reduce the costs of these credits by phasing out the benefit earlier and more rapidly and potentially by reserving the full benefits for low-income families. Lawmakers should also consider interactions and overlaps between the credits for young children in child care.

SALT Cap Relief: Lawmakers continue to discuss repealing or loosening the $10,000 cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, a policy that would be extremely regressive. As our recent analysis on the subject shows, less than 1 percent of the benefit of SALT cap repeal would go to the bottom 60 percent of the earnings distribution, while 92 percent of the benefit would go to those in the top quintile, and more than half would go to the top 1 percent. As we have shown before, there is really no version of SALT cap relief that would be well-targeted since the deduction almost exclusively benefits high earners. To help the few middle class (but mostly upper-middle class) families who are significantly affected by the SALT cap, policymakers could lift the cap below $100,000 of income and fully phase it in at around $150,000 of income. A better approach would be to phase out the SALT deduction itself (reducing the cap to zero) for high-income households.

Other Proposals: A number of other elements in reconciliation could be means-tested or better targeted. For example, President Biden has proposed making community college tuition-free at an estimated cost of $88 billion. While community college enrollment is relatively low among those from high-income families, phasing out the benefit at higher incomes could still lead to better targeting. Similarly, better targeting the House Education and Labor Committee's affordable child care proposal — which limits child care costs on a sliding scale to no more than 7 percent of income for families making up to twice their state's median income ($100,000-$190,000 in 2019) — could reduce costs and improve the economic benefit of providing affordable child care, especially if the income limit on subsidies is lifted (as is being considered in mark-up). In the health care space, policymakers are poised to extend beyond 2022 an expansion of the Affordable Care Act premium subsidies that limit premiums to a sliding scale percent of income target up to 400 percent of poverty ($125,000 for a family of five) but aim to limit premiums for all enrollees at and above that level to 8.5 percent of income. Continuing to increase that income cap with income could reduce costs and better target benefits. Finally, lawmakers could make sure various consumer incentives related to clean energy are well-targeted and not excessively subsidizing wealthy Americans for choices they already made.

With upwards of $5.5 trillion of policies currently under consideration, better means-testing and targeting is unlikely to be enough to reduce reconciliation spending to match revenue and offsets (which should be pursued aggressively). But it can help to get part of the way there and to make sure new spending and tax breaks are going where they will do the most good.

Read more options and analyses on our Reconciliation Resources page.

1These child tax credit numbers apply to the entire credit, not just the increase that lawmakers are considering extending in reconciliation. Technically, the $250,000 family would not receive anything from the ARP increase/reconciliation extension alone but would receive the prior law $2,000 credit, which only starts to phase out at income levels nearly three times higher than ARP's phaseout. However, even if the ARP phaseout schedule were applied to the entire $3,000/$3,600 credit, the CTC would still provide a $5,200 benefit to the $250,000 family and wouldn't phase out completely for that family until their income reached $354,000.