An Apples-to-Apples Comparison of the FY 2015 Budgets

Every year when the President releases his budget, CBO re-estimates the budget using a baseline set of economic assumptions – the same as it uses for measuring Congressional legislation. This year, they found that the President's budget would reduce deficits by about $500 billion less than the budget itself indicated, because CBO scored some provisions as saving less or costing more than the President claimed. In addition, the budget's debt as a percent of GDP looked worse because OMB had more favorable economic growth, raising the denominator in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

While CBO re-estimates the President's budget, they do not provide estimates of the Congressional budgets, since they only set targets and do not actually have to provide policies to meet those targets. In order to compare the budgets on an apples-to-apples basis, we estimated how all of the budgets would look if they relied on the same economic assumptions and CBO baseline and substituted estimates of policies where possible for the budgets' own stated savings. However, neither Senate Democrats nor Senate Republicans are planning to pass a budget this year, abdicating one of their yearly responsibilities. As a result, none of these budgets will become law.

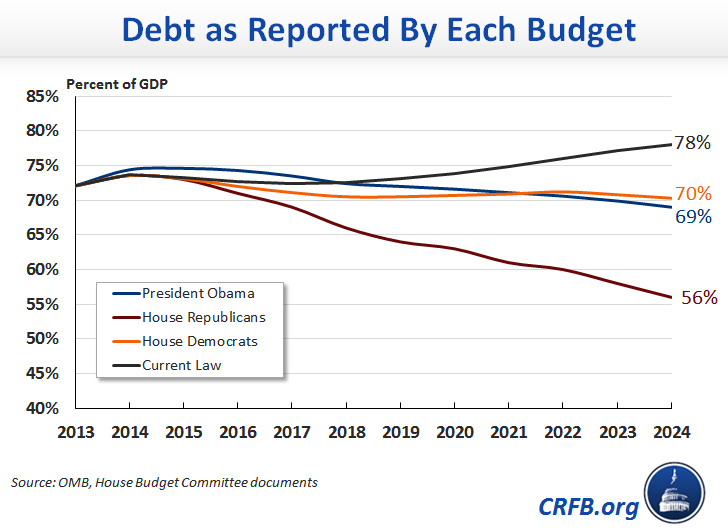

According to each budget's own numbers, all of them put debt on a downward path, rather than having debt increase to 78 percent of GDP by 2024. The President's and the House Democratic budgets have similar targets, putting debt on a modest downward path. The House Republican budget makes deep cuts in nondefense spending sufficient to bring debt much lower by the end of the decade.

However, the budgets are not strictly comparable: they all use different baselines. Even a basic measure like debt as a percentage of the economy is not comparable since each budget includes different estimates of economic growth from enacting policies. In the case of the President's budget, CBO found that things are less rosy than OMB: debt stayed at 2014 levels of 74 percent of GDP instead of decreasing to 69 percent. We tried to make similar calculations for the two main House budgets, using the same economic assumptions and using the latest baseline from CBO. We found that the House Democratic budget would climb to 73 percent, rather than fall to 70 percent. The Republican budget is nearly the same, but does not decline quite so much as it claims – to 57 percent of GDP rather than 56.

Although these re-estimates, on net, increase the amount of debt under each budget, there are factors that both increase and decrease savings in the two House budgets. (See our paper for a breakdown of CBO's changes to the President's estimates.) Most of the difference in both of these budgets is in the economic assumptions: the House Republicans' budget includes the economic effects of deficit reduction, while the House Democrats' budget includes the economic benefits of immigration reform. Removing the related budgetary effects that the Republican budget assumes and adjusting both budgets' GDP numbers raise debt as a percent of GDP.

In addition, we updated the estimates to use April's CBO baseline instead of February's. Ten-year baseline deficits were almost $300 billion lower in April, largely due to lower projected spending on health and the Affordable Care Act. Both budgets included savings from drawing down troops in Iraq and Afghanistan (the Republican budget would mirror the President's drawdown schedule, while the Democratic budget calls for zero spending on overseas contigency operations past 2015), savings which are lower when re-estimated by CBO.

Further, we've adjusted some scores for specific policies where we could, although the budgets do not provide specific numbers for many of them. On the Republican side, we reduced the savings from repealing the Affordable Care Act coverage provisions, since CBO's cost estimate of those coverage provisions decreased. On the Democratic side, we used CBO's newer (and more expensive) estimates of enacting a permanent doc fix and extending the refundable credit expansions. The Democratic budget also includes the same amount of increased revenue as the President's budget (without endorsing the President's specific policies), so we reduced the amount of revenue to reflect the amount that CBO scored for the President's policies.

The budgets themselves all claim to reduce the debt, but in fact do less when measured by the standards used by CBO. It is important that all the budgets are measured consistently, or it will be difficult to figure out whether they accomplish the goals they intend to reach. Coming up with a solution to our debt problems can start with something as simple as measuring plans against the same yardstick.