7 Takeaways from the President's FY 2023 Budget

President Biden released his Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 budget request this week, and there is a lot to unpack (see our full analysis). Below are seven key takeaways:

- A Welcomed Pivot to Deficit Reduction

The Administration’s new focus on deficit reduction is welcome news given the stronger economy, low unemployment, high inflation, and unsustainable debt. The budget’s proposed $1 trillion of net savings is an important first step and an improvement from last year’s budget, which proposed increasing deficits by $1.4 trillion over a decade. Its deficit reduction would come from $2.5 trillion of revenue and $65 billion of budget savings (offset by $1.5 trillion of new costs), with the largest offsets including increases in corporate and individual tax rates, a new minimum tax on unrealized income from high-wealth individuals, and closing a variety of tax breaks and loopholes for fossil fuel companies and others.

On top of this specified deficit reduction, encouragingly, the budget notes that the President "is committed to working with the Congress on legislation that both cuts costs for families and reduces the Federal deficit." If such legislation dedicates even half the savings from the House-passed Build Back Better Act to deficit reduction, it would nearly double the net savings of the President’s budget and prevent debt from reaching record levels at the end of the decade.

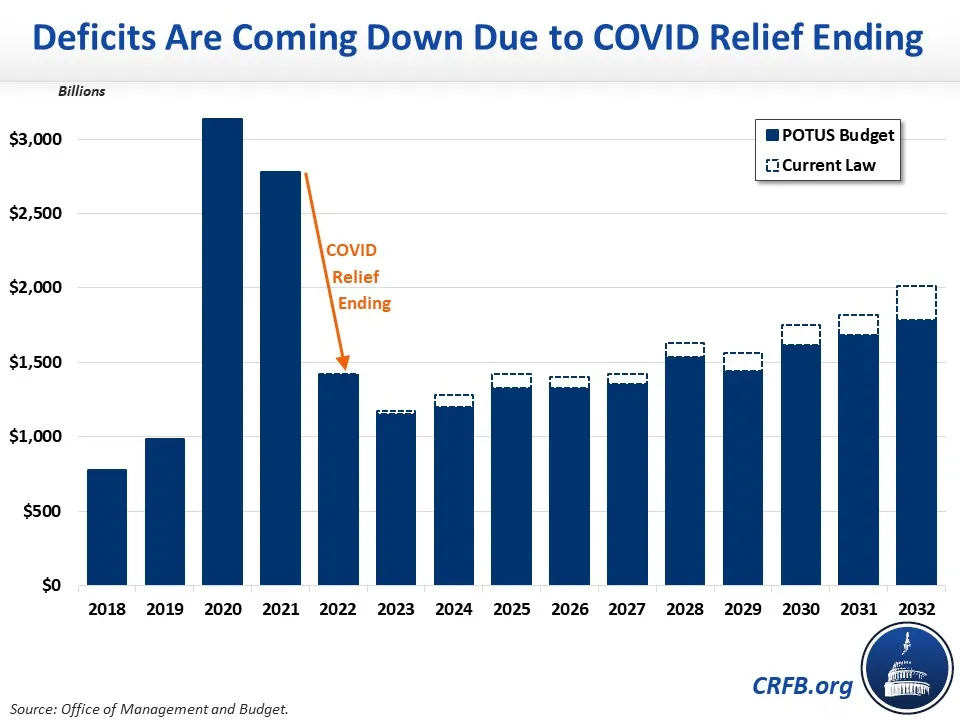

The newfound focus on deficit reduction is important both in terms of the emphasis the President puts on the issue and the policies he advocates for. We hope the President focuses on the need for more deficit reduction, rather than emphasizing the lower deficits that have already occurred due to waning COVID relief and economic improvements.

- Too Much Borrowing, Too Much Debt

Despite its proposed deficit reduction, the President’s budget still allows $14.4 trillion in borrowing over the next decade, and annual deficits would never drop below $1 trillion or 4.5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By the end of the decade, debt would reach a record 106.7 percent of GDP – the highest level in the nation’s history and well above the average of 44 percent for the past half-century. While this is lower than the Administration’s baseline estimate of 110 percent of GDP, it is still much too high.

The President and Congress have already added at least $2.5 trillion to deficits since the beginning of President Biden’s term. Much more deficit reduction would be needed just to cover those costs, let alone put the debt on a more sustainable path.

Deficit Increases During President Biden's Term So Far

| Enacted Policy | 2021-2031 Fiscal Cost |

|---|---|

| American Rescue Plan | $1,850 billion |

| Bipartisan Infrastructure Law | $400 billion |

| Expansion of SNAP Benefits (EO) | $180 billion |

| Extension of Student Debt Forbearance (EO) | $70 billion |

| Total, Deficit Increases | $2.5 trillion |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Note: Estimates exclude the effect of the FY 2022 omnibus appropriations bill, which increased the deficit by roughly $500 billion relative to CBO’s July 2021 baseline but would be roughly budget neutral relative to inflation. EO = Executive Order

The Administration’s effort to take credit for a decline in the deficit is particularly misleading, given that this is merely the deficit falling from the economy returning to normal and COVID relief coming to an end.

It will take much more than $1 trillion in deficit reduction to bring our debt down to manageable levels. For example, it would take $3.5 trillion in ten-year savings to stabilize the debt at 100 percent of GDP by 2032 and could require roughly $6.5 trillion to achieve primary balance (balance excluding interest payments) by 2032. Restoring the debt to its pre-COVID level of 80 percent of GDP over two decades by reducing it by roughly 1 percentage point per year would require roughly $7 trillion of deficit reduction over a decade.

Required Savings to Reach Certain Fiscal Goals (2023-2032)

| Fiscal Goal | Ten-Year Savings Required |

|---|---|

| Deficit Reduction in the President's Budget | $1.0 trillion |

| Stabilize Debt at 100% of GDP by 2032 | $3.5 trillion |

| Primary Balance by 2032* | $6.5 trillion |

| Restore Debt to 80% of GDP by 2042^ | ~$7.0 trillion |

Source: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimate. All estimates include interest and are relative to OMB’s baseline in the Presidents’ budget.

*Assuming path of major deficit-reduction policies in budget and Build Back Better with no spending increases or tax cuts. ^Assumes debt is reduced to 90 percent of GDP by 2032.

- A Missing Centerpiece

Absent from the President’s budget is the core item of his agenda: all of the policy proposals that made up the House-passed Build Back Better Act. This includes proposals to combat climate change, support affordable child care and long-term care, expand health insurance coverage, offer paid leave, provide free preschool, and revive a variety of expanded tax credits, among other changes. Instead of these new proposals, the budget includes a deficit-neutral reserve fund that it claims could be more than offset with policies that lower prescription drug costs and raise taxes on wealthy Americans and corporations.

While the budget explains this decision was made in order to allow for ongoing discussions with Congress, the result is a budget that does not reflect the bulk of the President’s priorities. This removes up to $2 trillion in costs and $2 trillion in offsets that are simply not accounted for. It is impossible to evaluate a budget based around an agenda that is completely absent, and it renders the budget somewhat meaningless.

Ironically, many of the policies in the budget are ones that were effectively rejected by Congress in earlier rounds of Build Back Better negotiations. The Build Back Better package would be much better evaluated inside of the budget instead of being a magic asterisk adjacent to it.

- A Late Budget with Dated Economic Assumptions

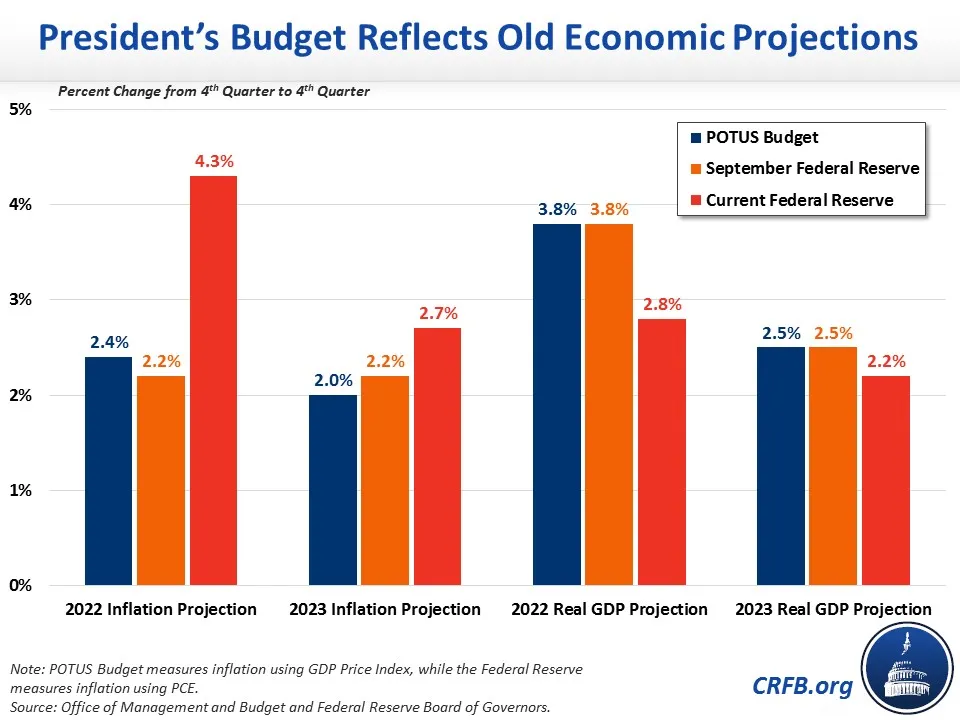

While the President’s budget is due the first Monday of February, this year’s budget was released nearly two months after that deadline. In part because the budget release was so delayed, the economic assumptions within the budget were long out of date by the time of release. The inflation, economic growth, interest rate, and employment assumptions that underlie the budget and its estimates were based mainly on data from October of 2021 – five months before the budget was released.

In some cases, these differences are quite large. The budget assumes real GDP growth of 3.8 percent in 2022, which is in line with Federal Reserve forecasts at the time but much higher than the 2.8 percent growth the Fed is currently forecasting. Similarly, the budget assumes 2.4 percent inflation for 2022, based on the GDP price index; the Federal Reserve is now forecasting inflation of 4.3 percent, using a similar measure.

While it is uncertain just how different the budget’s projections would be with updated economic assumptions, it does underline just how broken the budget process has gotten. Had Congress followed its own schedule for passing appropriations on time, and had the President’s budget been submitted in February, we might have at least had a budget that reflected assumptions at the time – not one based on data from nearly half a year ago.

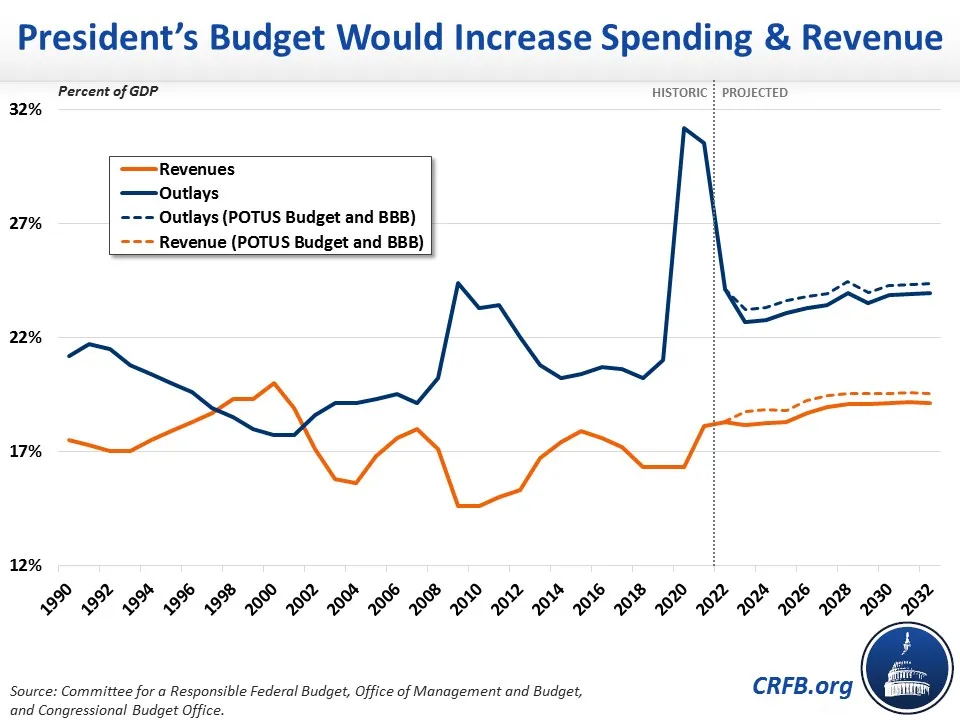

- A Larger Federal Government

The President’s budget would substantially increase the size of government. Even excluding the effects of Build Back Better, the budget would increase spending by $1.4 trillion and revenue by $2.5 trillion. By the end of the decade, spending would reach 23.9 percent of GDP – the highest in post-war history other than during the global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic. Revenue would reach 19.1 percent of GDP, higher than any other year besides 1981 and 1998 through 2000.

Importantly, these figures understate revenue and spending increases by excluding all parts of the Build Back Better agenda. As an illustrative example, if that agenda included $150 billion of spending and revenue per year, the budget would increase spending by nearly $3 trillion and revenue by $4 trillion. In this scenario, spending would reach 24.3 percent of GDP in 2032 and revenue would reach 19.5 percent. Of course, any revenue raised to finance this new spending would be unavailable to finance existing spending and address our existing large fiscal imbalances.

- Helpful Ideas to Put More Revenue On the Table

Putting the country on a sustainable path is going to require higher tax revenue. The President’s budget puts forward more than $2.5 trillion of policies that raise taxes, improve compliance, reduce tax breaks, and close tax loopholes. This does not include any of the $1.6 trillion of revenue proposals in the House-passed Build Back Better Act.

Revenue Proposals in the President's FY 2023 Budget

| Policy | Revenue Raised |

|---|---|

| Increase corporate tax rate to 28% (assuming 20% global minimum tax) | $1,315 billion |

| Establish a 20% minimum tax on unrealized capital gains for the wealthy | $360 billion |

| Reform taxation of foreign business income | $240 billion |

| Increase the top individual income tax rate to 39.6% | $195 billion |

| Tax capital gains as ordinary income for high-income earners and tax gains at death | $175 billion |

| Close Estate Tax loopholes | $50 billion |

| Eliminate fossil fuel tax preferences | $45 billion |

| Other revenue proposals | $170 billion |

Source: Office of Management and Budget.

Among its proposals, the budget calls for raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent, restoring the top individual tax rate to 39.6 percent, closing a variety of estate tax loopholes, and limiting stepped-up basis of capital gains at death. The budget also calls for a new 20 percent minimum tax for very wealthy households that require them to pre-pay some capital gains taxes as assets appreciate over time rather than waiting for their sale.

The budget also closes loopholes and tax breaks related to carried interest, fossil fuel production, gains from property sales, digital asset trading, and conservation easements, among other areas. The President should be commended for putting forward these policies, which can be used by Congress to reduce budget deficits or fund new spending and tax breaks.

- Missing Health Savings, Trust Fund Solutions, and Discretionary Caps

Inflation continues to surge in the near term, while the long-term growth of health care costs – along with the aging of the population – threatens our budget and major trust funds. The Social Security, Medicare, and the Highway trust funds are all projected to be insolvent in the next 12 years. Yet the President’s Budget does little to address either rising health costs or major trust fund programs.

Budgets from Presidents Trump and Obama both put forward hundreds of billions of dollars of health care savings, including overlapping proposals to equalize payments for similar procedures, address excessive post-acute care payments, and enact other reforms. While the Build Back Better Act would substantially reduce prescription drug costs, the budget itself includes only $20 billion of total health care savings.

Nor does the budget include any major policies to raise revenue or adjust benefits to improve the solvency of Social Security, Medicare Hospital Insurance, or the Highway Trust Fund. Without action, people who rely on those programs will face abrupt across-the-board cuts.

Additionally, the budget does not incorporate a serious plan to control defense and nondefense discretionary spending. Arguably the most important function of the President’s budget is to suggest spending levels for these appropriations, which the President's budget does. But it would be far improved by proposing statutory caps on discretionary spending for the next decade. Setting reasonable caps encourages fiscal discipline and ensures that any needed increases are paid for.

***

There is much to like and dislike about what is in – and what is missing from – the President’s FY 2023 budget proposal. We’ll be continuing to analyze the President’s budget over the coming days.

Note (4/1/2022): An earlier version of this analysis misstated the fiscal goal year for reducing debt to 80 percent of GDP. It has been corrected.