Analysis of CBO's February 2021 Budget and Economic Outlook

Today, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its February 2021 Budget and Economic Outlook, confirming that, despite improvements as a result of stronger than expected economic growth, the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis has deteriorated our already grim fiscal outlook. CBO’s report shows:

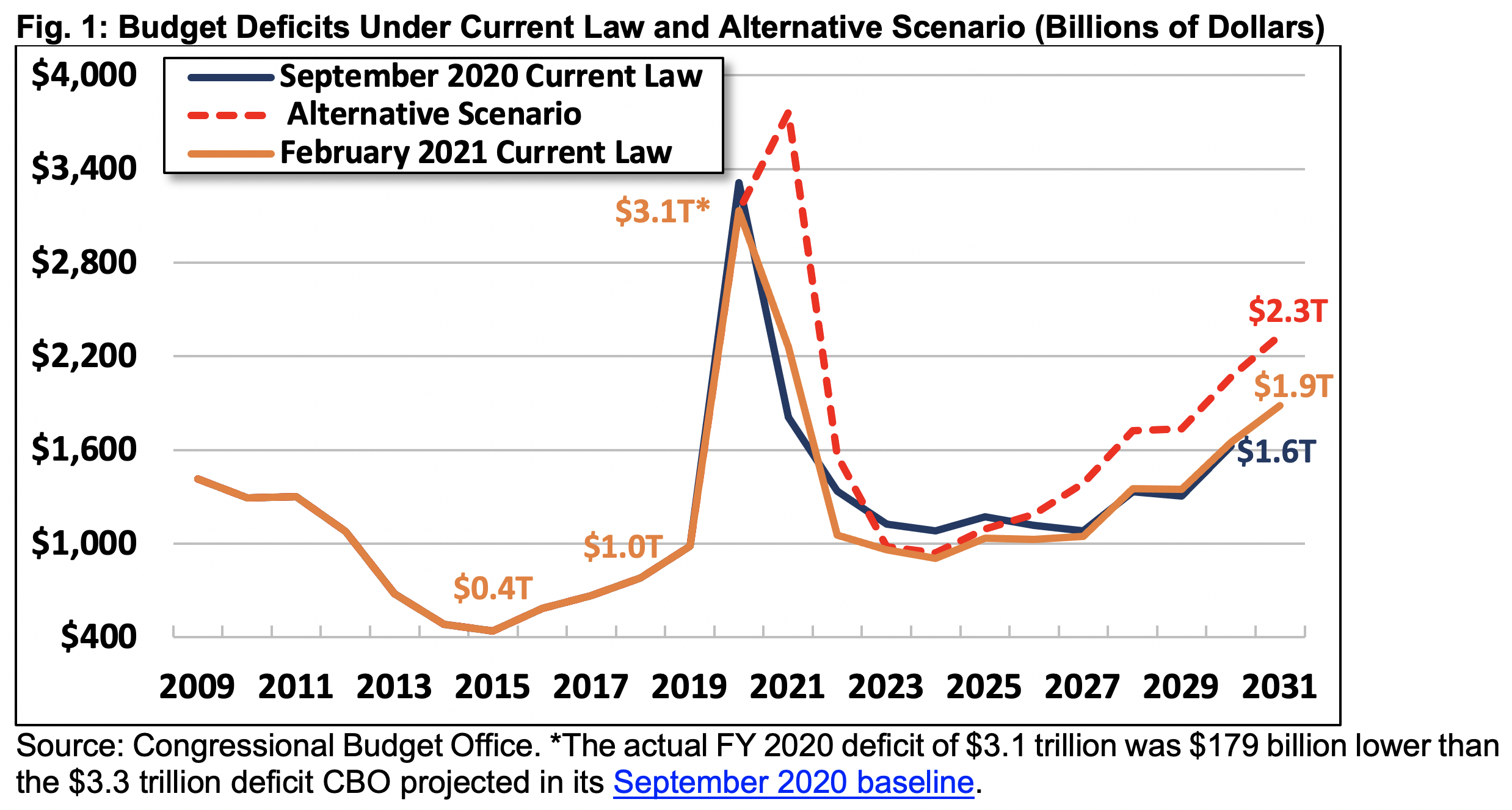

- The budget deficit will total $2.3 trillion – 10.3 percent of GDP – in FY 2021 and total $12.3 trillion (4.4 percent of GDP) over the next decade. The deficit will fall from these highs, but rise back to $1.9 trillion (5.7 percent of GDP) by 2031.

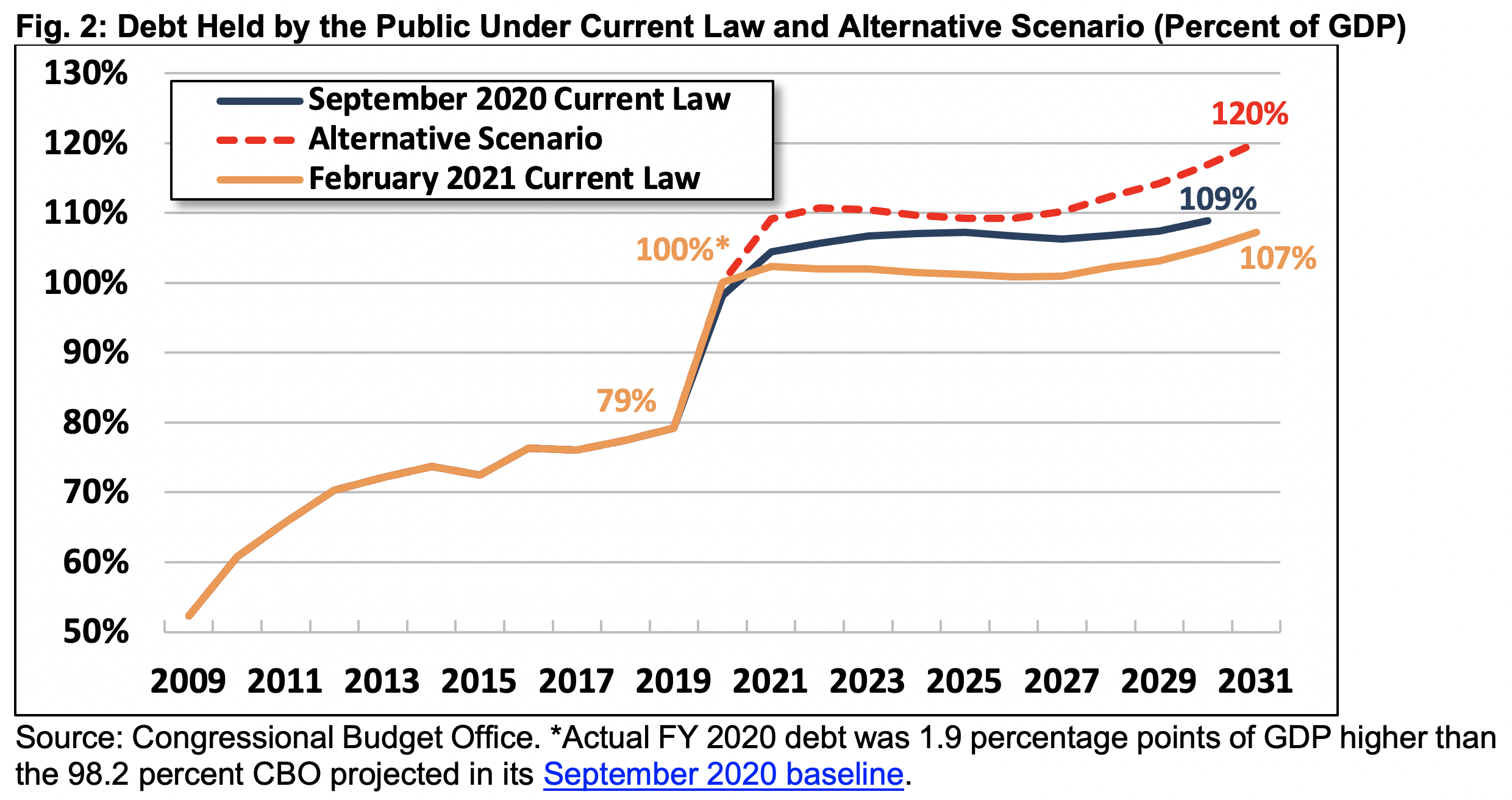

- Debt will reach a new record as a share of the economy, growing from over 79 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2019 to over 102 percent of GDP by the end of 2021, and more than 107 percent of GDP by the end of 2031. In nominal dollars, federal debt held by the public has grown by $4.9 trillion since the end of FY 2019 and will grow another $13.6 trillion by the end of 2031, ultimately reaching $35.3 trillion.

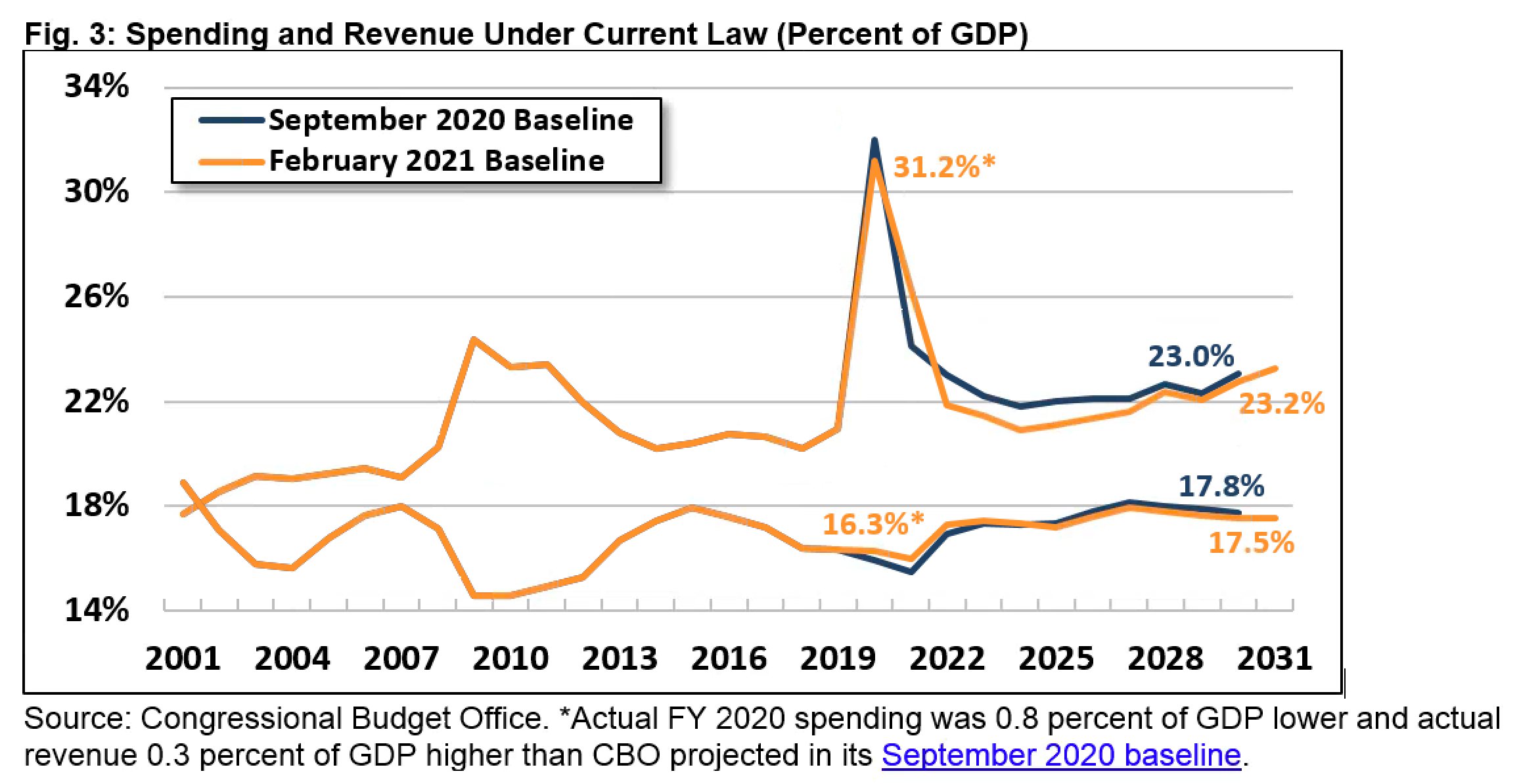

- The projected growth in debt and deficits is driven by a disconnect between spending and revenue. Revenue will total 16.0 percent of GDP in 2021 and average 17.5 percent over the subsequent decade – around its historic average of 17.3 percent. Spending will total 26.3 percent of GDP in 2021 and average 21.9 percent from 2022 to 2031, above its historic average of 20.4 percent.

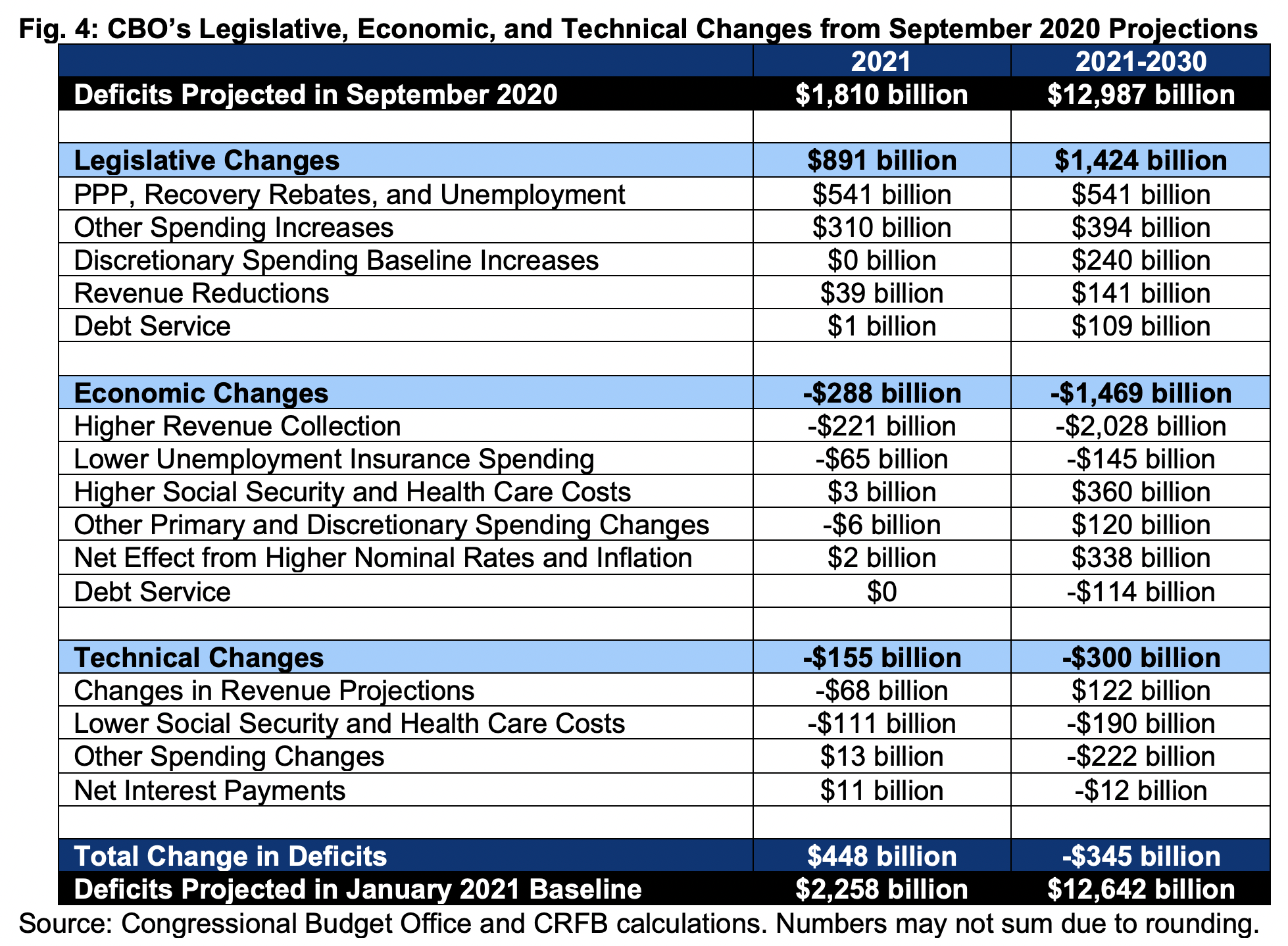

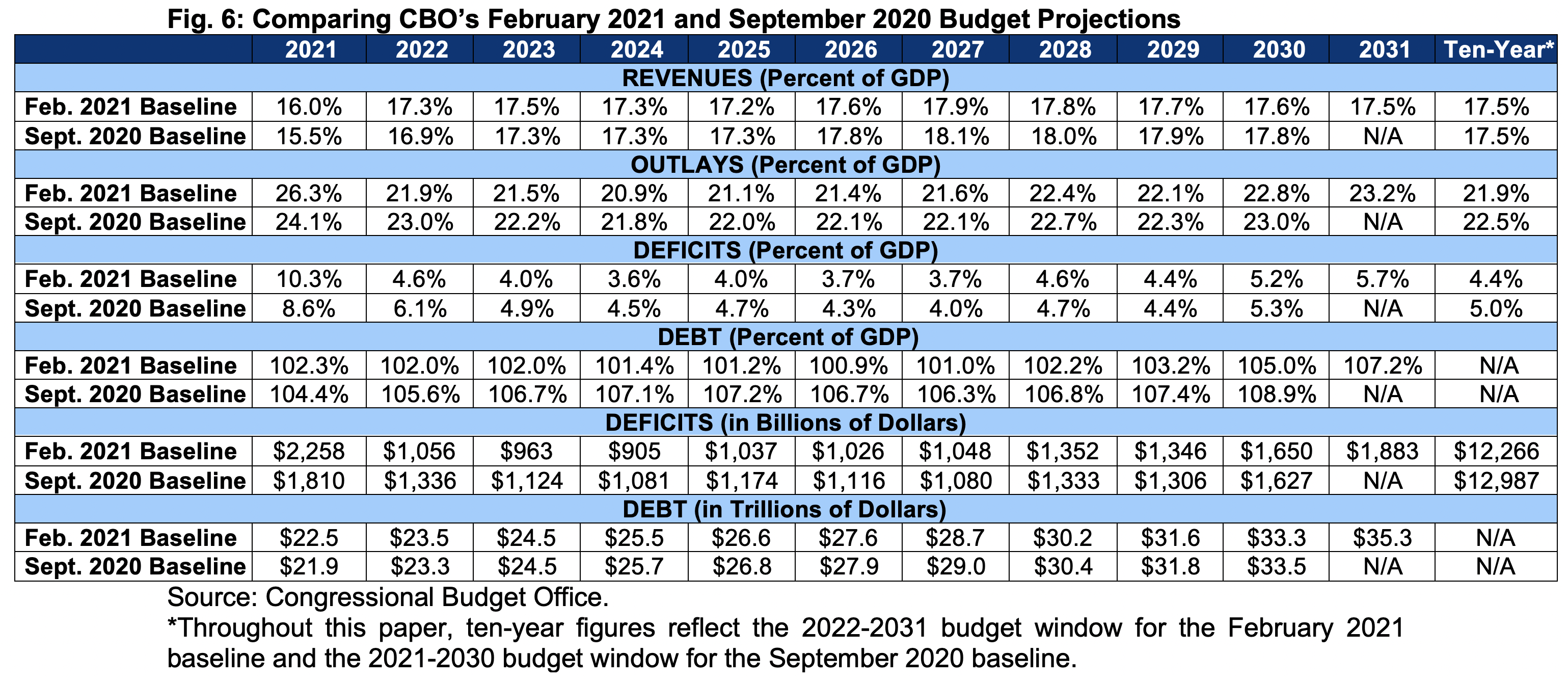

- Deficits through 2030 will be $345 billion lower and debt to GDP in 2030 will be four percentage points lower than CBO projected in September. While the December COVID relief and omnibus package added $1.4 trillion to the deficit through 2030, improvements in the economy and other factors reduced deficits by $1.8 trillion over the same period.

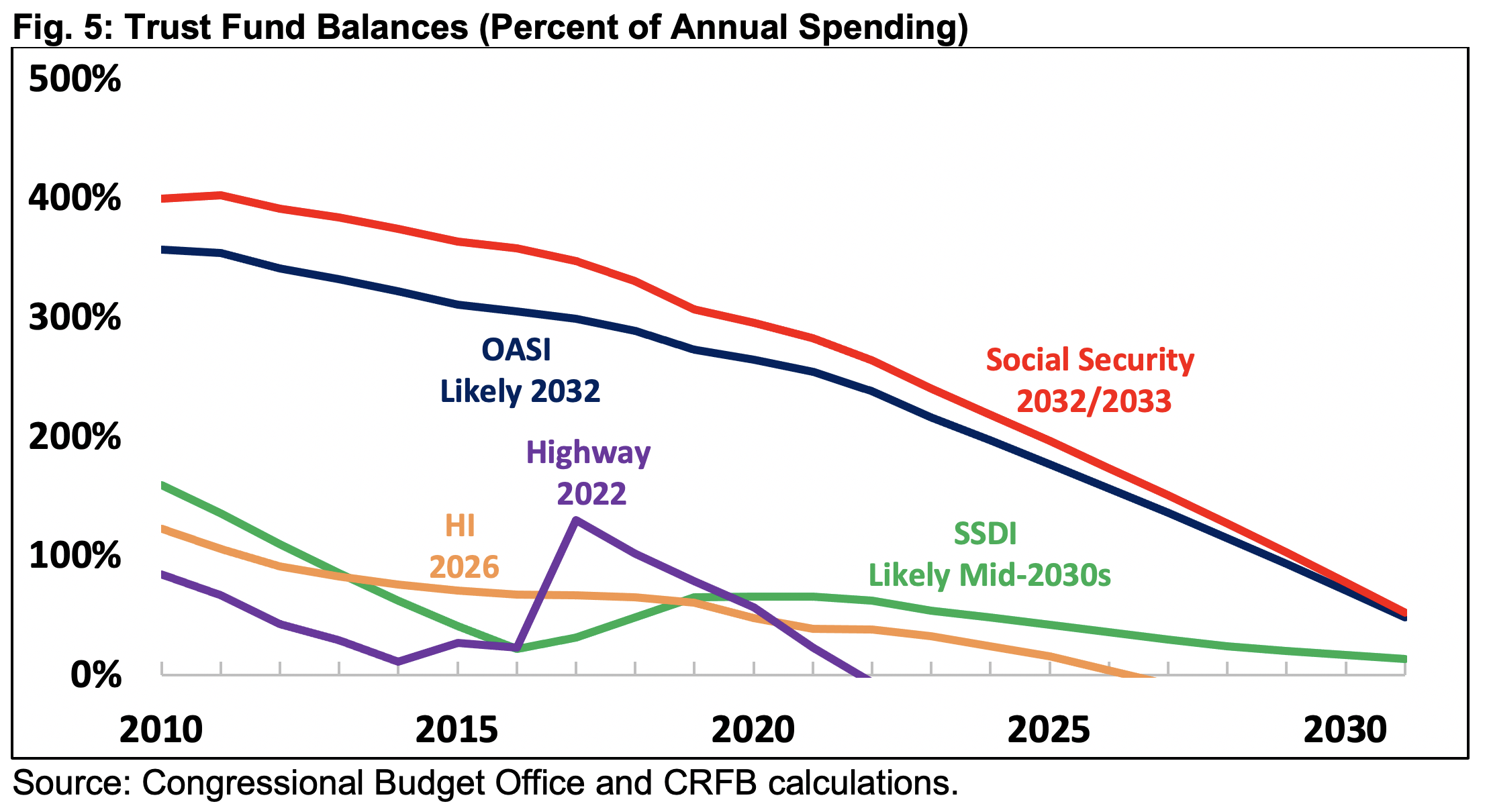

- Four major trust funds are on a path toward insolvency. CBO projects Highway Trust Fund insolvency in FY 2022, Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund insolvency in FY 2026. Social Security Old Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund insolvency appears likely in calendar year 2032 and Social Security Disability Insurance trust fund insolvency in the mid-2030s.

- Debt could be even higher than projected. If policymakers enact $2 trillion of additional fiscal relief, extend expiring tax provisions, and grow annual appropriations with GDP, debt would total 120 percent of GDP by 2031.

The United States is Facing Large Deficits

CBO projects high annual budget deficits under current law. After more than tripling to $3.1 trillion (14.9 percent of Gross Domestic Product, or GDP) in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, CBO projects the deficit will total $2.3 trillion (10.3 percent of GDP) in 2021, fall to a low of $905 billion (3.6 percent of GDP) in 2024, and grow to $1.9 trillion (5.7 percent of GDP) in 2031.

Even without further COVID relief, this year’s deficit in nominal dollars will be the largest in history other than last year’s. As a share of GDP, the 2021 deficit will be the sixth highest in history, eclipsed only by last year and four years of borrowing to fight World War II.

Over the 2022-2031 budget window, deficits will total $12.3 trillion and average 4.4 percent of GDP per year. This is well above the historic average of 3.3 percent of GDP.

Deficits could be even higher if lawmakers enact further COVID relief and continue their pre-COVID streak of fiscal irresponsibility. In our alternative scenario, we assume lawmakers enact an additional $2 trillion of fiscal support to combat the current crisis, extend most expiring tax cuts, and grow appropriations with the economy rather than inflation.

Under this alternative scenario, deficits would total $15.0 trillion (5.4 percent of GDP) over the 2022-2031 budget window. They would total between $3.5 and $4 trillion (16 to 18 percent of GDP) this year – a new record – and $2.3 trillion (7.1 percent of GDP) in 2031 alone.

Debt Will Grow to Record Levels

At the end of FY 2020, federal debt held by the public eclipsed the size of the economy for the only time in history outside of the World War II era.

Under current law, CBO estimates that, between the end of FY 2019 and the end of FY 2021, debt will have increased from over 79 percent of GDP in 2019 to over 102 percent of GDP in 2021. Assuming no additional fiscal relief is enacted, CBO projects debt remain relatively stable as a share of GDP through 2026 as the economy recovers from the current crisis before ultimately rising again to over 107 percent of GDP by 2031. This would represent a new record, surpassing the prior record of 106 percent of GDP set just after World War II.

In nominal dollars, debt has grown by $4.9 trillion since the end of 2019 and CBO estimates it will grow by another $13.6 trillion through the end of 2031 to a total of $35.3 trillion.

The relatively stable debt level between 2020 and 2025 is partially a function of Treasury’s cash management strategies, a sharp reduction in GDP in 2020, and a temporary acceleration of economic growth as the economy recovers. Whereas debt-to-GDP only rises one percentage point (from 100 to 101 percent of GDP) between 2020 and 2026 under CBO’s baseline, debt net of financial assets as a share of potential GDP will rise by 10 percentage points (from 83 to 93 percent of potential GDP).

Debt levels could be significantly higher if lawmakers enact additional fiscal support, extend various expiring tax cuts, and grow annual appropriations with the economy. Under our alternative scenario, debt would grow an additional $4.3 trillion to almost $40 trillion, or 120 percent of GDP, by 2031.

Spending and Revenue Will Continue to Diverge

Rising debt and deficits are driven by a disconnect between spending and revenue. Between 2021 and 2031, CBO projects spending will total $67.0 trillion (22.3 percent of GDP) while revenue will total $52.5 trillion (17.4 percent of GDP). In other words, projected revenue will only be enough to cover a little more than three-quarters of projected spending.

As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, CBO projects spending grew from $4.4 trillion (21.0 percent of GDP) in 2019 to $6.6 trillion (31.2 percent of GDP) in 2020 and will total $5.8 trillion (26.3 percent of GDP) in 2021 under current law. As the country recovers from the current crisis, CBO expects spending to fall below 21 percent of GDP by 2024 before rising to 23.2 percent of GDP by 2031.

On the revenue side, CBO estimates receipts have remained roughly flat since 2019 at roughly $3.5 trillion (16.0 percent of GDP) per year. CBO projects revenue will grow substantially between 2021 and 2022, to $4.0 trillion (17.3 percent of GDP), and then remain at about that level through 2031. CBO projects revenue will total $5.8 trillion (17.5 percent of GDP) in 2031.

Spending growth beyond 2025 is largely driven by rising costs of Social Security, health care, and interest payments. Revenue growth is driven by a growing economy and the scheduled expiration of many provisions in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, mostly beginning in 2026.

Spending could be higher and revenue lower if lawmakers enact additional fiscal support, extend various expiring tax cuts, and grow annual appropriations with the economy. Under our alternative scenario, revenue would reach only 16.5 percent of GDP by 2031, while spending would grow to 23.5 percent of GDP.

The COVID-19 Pandemic Continues to Weigh on the Budget Outlook

Under current law, CBO projects deficits will be $345 billion and 0.1 percent of GDP lower over the 2021-2030 budget window than it forecast in September. This is the net effect of lower deficits from CBO’s stronger economic forecast and higher deficits from recent legislation.

Legislative changes have increased deficit projections by $1.4 trillion. Most of this increase is the result of more than $900 billion of COVID relief and almost $150 billion of new tax breaks and extenders. Roughly $240 billion is the result of assumed higher discretionary spending in future years, as a result of the omnibus bill, and the remaining $100 billion reflects higher interest costs.

Economic improvements have reduced projected deficits by $1.5 trillion. CBO’s latest economic forecast is a substantial improvement from its July forecast — estimates of real GDP, income, price levels, and interest rates are all higher. As a result, CBO projects $2.0 trillion of greater revenue collection and $145 billion less in spending on unemployment benefits, but also $585 billion more in spending on Social Security, health care, and net interest payments.

Finally, CBO projects $300 billion less in deficits from technical changes. This is driven mainly by lower expected Social Security, health care, and food stamp costs – but also by nearly $70 billion in unexpected receipts from spectrum auctions.

Major Trust Funds Are In Trouble

A number of important federal programs are financed through dedicated revenue sources and managed through federal trust funds. Under CBO’s new baseline, two major trust funds will exhaust their reserves in the next five years, and the Social Security trust funds will likely become insolvent in the early-to-mid-2030s.

Specifically, CBO projects the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) will deplete its reserves in 2022 and the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund in 2026. Both the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust funds are projected to remain solvent through 2031 but will have declining trust fund balances throughout the decade. Based on their trajectories, it appears that the OASI trust fund will likely be exhausted in calendar year 2032, while the SSDI trust fund will run out a few years later in the mid-2030s.

Absent new legislation, highway spending would be cut by about one-fifth and Medicare hospital spending by 13 percent upon insolvency of the HTF and the HI trust fund, respectively. Assuming OASI becomes insolvent in 2032, today’s youngest retirees would face a sharp 25 percent drop in their benefits when they turn 73.

CBO’s current estimates are more favorable than the ones it published in September. Insolvency dates have been pushed back one year for the Highway Trust Fund and Social Security Old Age programs, two years for Medicare Hospital Insurance, and approximately a decade for Social Security Disability. These improvements mainly reflect higher projected revenue but also a general revenue transfer into the Highway Trust Fund, higher interest rates, and other changes.

Conclusion

CBO’s latest budget projections confirm what we have warned about for some time: our country is on an unsustainable fiscal path and the budget outlook will continue to deteriorate as a result of irresponsible tax and spending policies, which predate the COVID-19 crisis, and the growth of health and retirement spending. The response to the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis, though necessary to stabilize the economy and limit human suffering, has further increased deficits and debt.

Even after the short-term emergency is over, our longer-term challenges remain. Under current law, the deficit will decline from a record high of $3.1 trillion (14.9 percent of GDP) at the end of FY 2020 to $2.3 trillion (10.3 percent of GDP) this year and below $1 trillion by the middle of the decade before rising again to $1.9 trillion (5.7 percent of GDP) in 2031. Largely as a consequence of rosier economic growth projections, deficits through 2030 will be $345 billion lower than CBO projected in September, but are troubling nonetheless.

For the first time in our history outside of World War II, the debt is now larger than the economy. CBO projects it will remain at this elevated level for several years, ultimately rising to a new record of 107 percent of GDP by 2031.

These projections assume current law remains unchanged. However, if lawmakers enact $2 trillion in further COVID relief as anticipated and extend costly tax and spending policies, debt would rise to 120 percent of GDP by 2031. In either case, debt is projected to rise unsustainably over the long-term.

Once the current crisis ends and the economy is well on its way to recovery, policymakers must turn their attention to long-term debt and deficit reduction to get the country on solid fiscal ground. This includes action to secure Social Security and other trust funds headed toward insolvency, limit the growth of health care and other costs, and raise additional tax revenue.

Policymakers should also work to put the country in a better fiscal and economic position so that we can be better prepared for future challenges.

Appendix

What's Next

-

Image

-

-

Image