The Federal Tax Benefits for Nonprofit Hospitals

More than half of the nation’s hospitals are designated as “charitable” nonprofit institutions by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), exempting them from most federal, state, and local taxes and making donations to them eligible for a tax deduction.

Linked to this status is the requirement that nonprofit hospitals will deliver benefits to the communities they serve. Such benefits can encompass a broad range of activities like charity care and financial assistance programs, local health improvement programs, and health professional education. However, there is insufficient enforcement of existing requirements and no unambiguous federal statutory or regulatory definition of “community benefits.”

Research consistently shows that nonprofit hospitals are failing to meet community benefit obligations under all but the broadest (many argue, overly expansive) definitions.1 Investigative reports highlight instances where such hospitals prioritize financial gains over community welfare, often neglecting those in need of financial assistance. Furthermore, evidence suggests nonprofit hospitals offer fewer community benefits compared to for-profit hospitals.

Given the substantial amount of revenue devoted to subsidizing nonprofit hospitals, policymakers should work towards reducing those subsidies and/or enforcing stricter requirements for substantial community benefit provision.

The Health Savers Initiative is a project of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Arnold Ventures, and West Health, which works to identify bold and concrete policy options to make health care more affordable for the federal government, businesses, and households. This brief presents an option meant to be just one of many, but it incorporates specifications and savings estimates so policymakers can weigh costs and benefits, and gain a better understanding of whatever health savings policies they choose to pursue.

The Tax Exemption and “Community Benefits”

Of the nation’s 5,129 community general hospitals, 2,987 (58 percent) are non-governmental, nonprofit institutions that are exempt from most taxation.2 There is no official government tally of the lost revenue from the tax exemption; however, researchers have used different methods to estimate the value of the exemption. KFF has produced the most recent estimate, suggesting that nonprofit hospitals collectively enjoyed $28.1 billion worth of tax exemptions in 2020 – $14.4 billion from federal taxes and $13.7 billion from state and local.3

Hospitals designated as 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations gain several advantages, including exemption from federal income taxes and various state and local taxes on net income, real property, and purchased goods. They may also access favorable borrowing terms akin to governmental entities, and donations made to them are tax-deductible on donors' federal income tax returns.

In 1956, the IRS first issued a standard requiring that in exchange for their nonprofit designation, hospitals should provide charity care “to the extent of [their] financial ability.”4 This requirement underscored the significant need for direct charity care at that time, given it predated the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid.

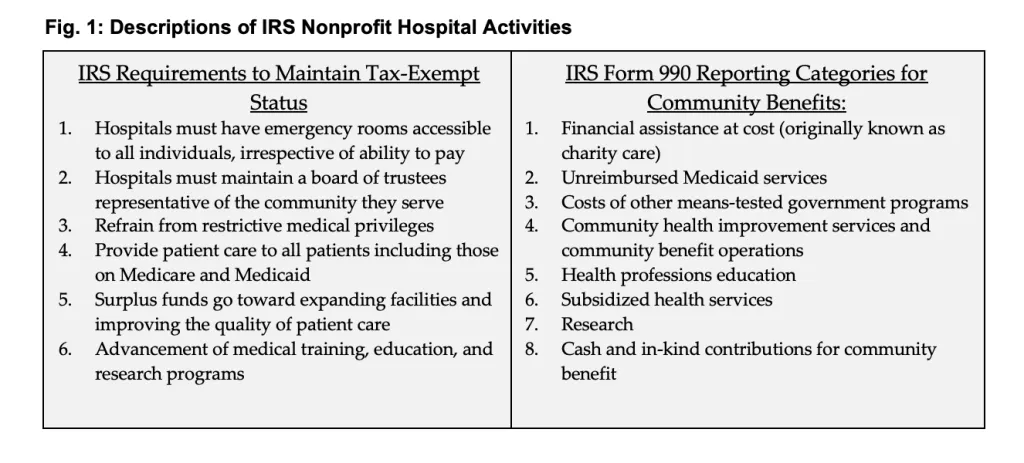

In 1969, in response to arguments from the hospital industry asserting that Medicare and Medicaid had diminished the necessity of charity care, the IRS revised its standard, shifting focus to the broader concept of "community benefits." Hospitals would now be required to demonstrate efforts in promoting the health of a class of persons who “represent the broad interests of the community served.”5 The IRS also stipulated six factors that hospitals should fulfill to maintain tax exempt status (see Figure 1).6 These criteria serve as benchmarks to ensure that tax-exempt hospitals are actively contributing to the welfare of the community.

For the subsequent 40 years, federal policy on community benefit saw no significant alterations. However, in 2009, the IRS introduced Schedule H to Form 990, allowing, but not requiring, tax-exempt hospitals to provide information on the nature and cost of community benefits.7 In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated increased transparency from nonprofit hospitals, with regular compliance monitoring by the IRS, and barred certain excessive billing and debt collection practices.8

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reviewed the landscape for federal nonprofit hospital regulations and summarized that despite the ACA’s additional requirements, “the law is (still) unclear about what community benefit activities hospitals should be engaged in to justify their tax exemption.”9 Furthermore, they found that the IRS has not enforced accountability, even for some hospitals that report no community benefit spending at all. IRS assessments often rely upon secondary data sources and hospital-reported information, and few hospitals have been referred for potential ACA violations.

GAO identified weaknesses in the structure of Form 990 community benefit standards, notably that benefit reporting is made only at the “hospital organization” level rather than the individual hospital facility level. This poses challenges to transparency, particularly in an era of hospital consolidation and growth of multi-hospital organizations, as it provides wide latitude for gaming reported benefit spending. In essence, GAO suggests the IRS could take more proactive measures to ensure that hospitals are complying with their obligations under the law.10

Hospitals’ Community Benefit Performance

There is no definitive benchmark for assessing community benefit spending. However, independent analysts have shown that nonprofit hospitals likely fail any test of community benefit sufficiency by delivering no more in the major categories of community benefit than do for-profit hospitals, and in total they do not deliver community benefits sufficient to justify their tax exemption.11

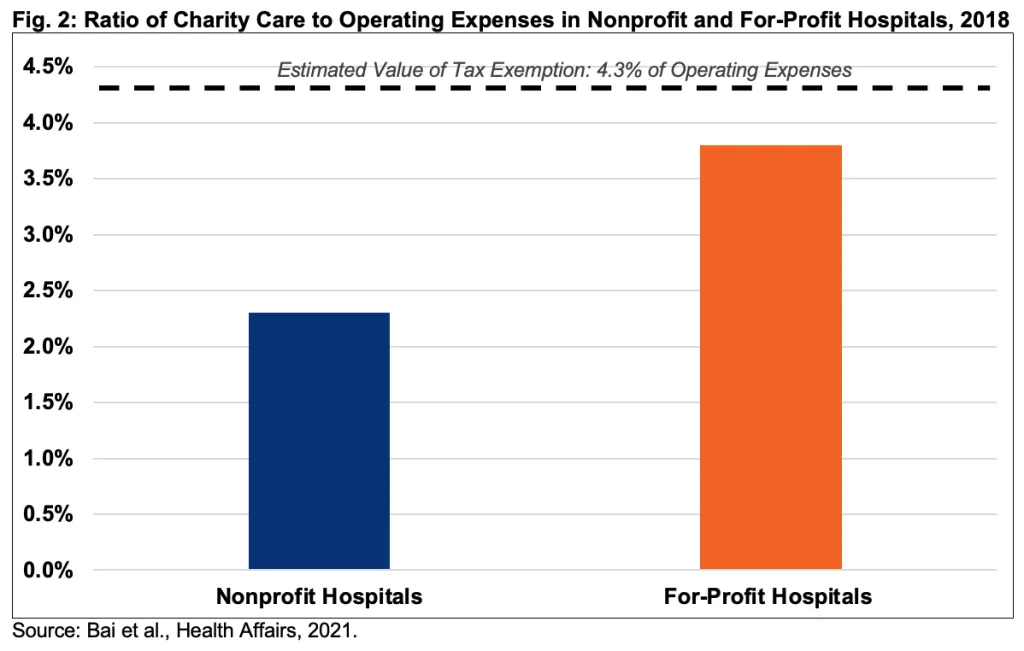

Examinations of hospitals’ community benefit performance have focused on both the original definition of the concept – charity care, the largest tangible category of benefit – and on broader measures of community benefits.12 For charity care, Figure 2 shows an analysis by Johns Hopkins University researchers that used data from 2018 to estimate the average charity-care-to-expense ratio of nonprofit and for-profit hospitals.13

Their analysis shows that nonprofits provide charity care at 2.3 percent of operating expenses, relative to an estimated value of the tax exemption of 4.3 percent of operating expenses.14 KFF found similar results in 2020 but noted the wide ranges in charity care provision. The top 9 percent of hospitals in delivering charity care spent 7 percent of operating expenses or higher. However, the 8 percent least charitable hospitals only gave charity care equal to 0.1 percent of operating expenses.15

Both studies also found that nonprofit hospitals generally provide less charity care than their for-profit counterparts, likely because for-profit hospitals can deduct charity care costs from taxes and have a vested interest in building their reputations in local communities, particularly in areas where they directly compete with nonprofit hospitals.

Media investigations have also targeted nonprofit hospital misconduct, particularly regarding charity care. As just one example, a 2022 investigative report by the New York Times featured Providence Health, a 51-hospital system on the west coast with revenues of $27 billion and $1.2 billion worth of tax exemptions. Despite earning substantially high net income, the hospital system’s charity care expenditures in 2018 amounted to just above 1 percent of operating expenses, well below the national average, and fell below 1 percent in 2021.16

Moreover, it failed to screen patients timely for eligibility for charity care, as required under its home state law of Washington, and it sought payment from thousands of patients who later were found to be eligible for free care. This aggressive collection approach led many patients to feel harassed, both by Providence and the collection agencies it enlisted, and resulted in damaged credit scores for some. Providence has certainly not been alone in this behavior – a research team looking at the 100 largest hospitals found that 26 of the hospitals filled collection lawsuits, of which 17 were nonprofits (eight were government-owned and one was for-profit).17

Broader analyses of community benefits that include spending beyond just charity care also suggest nonprofit hospitals are falling short relative to tax benefits. The nonpartisan Lown Institute produces an annual “Fair Share” measure as part of its hospital index and in 2024 found that “80 percent of nonprofit hospitals spent less on financial assistance and community investment than the estimated value of their tax breaks.”18 Other researchers have found similar results over a variety of time periods using a variety of methodologies.19

Questions about nonprofit hospitals’ performance in meeting expectations certainly are not new. In 2006, the Senate Finance Committee (SFC), then chaired by Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), launched an inquiry into nonprofit hospitals’ practices. The committee concluded, in part:

Non-profit doesn’t necessarily mean pro-poor patient. Non-profit hospitals may provide less care to the poor than their for-profit counterparts. They may charge poor, uninsured patients more for the same services than they charge insured patients. They sometimes give their executives gold-plated compensation packages and generous perks such as country club memberships. All of this calls into question whether non-profit hospitals deserve the billions of dollars in tax breaks they receive from federal, state, and local governments.20

Policymakers continue to worry that nonprofit hospitals are not meeting their community benefit obligations. In August 2023, Senators Grassley, Bill Cassidy (R-LA), Raphael Warnock (D-GA), and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) – two Democrats and two Republicans – wrote to the IRS Commissioner and the Treasury Department’s Office of the Inspector General seeking answers to questions about the performance of both hospitals and the oversight agency.21

The “Medicaid Shortfall” as a Form of Community Benefit

Defenders of the current system contend that their contribution to the community exceeds the value of their tax exemption by a significant margin. The American Hospital Association estimates that nonprofit hospitals provide four times the value of their tax exemption – $130 billion in 2020 alone of total community benefits.22

They arrive at this estimate utilizing an expansive, yet not convincing, definition of what qualifies as community benefits. Notably, hospitals add the value of what they consider to be the “Medicaid shortfall” to their claimed benefit spending. The concept is that the costs to deliver services to Medicaid beneficiaries – who today comprise about one in four Americans – exceed the payments they receive from the state and federal government for that care and thus the “shortfall” should count as a community benefit.

The Medicaid shortfall is one of the expenses that can be reported to the IRS on the 990 form and, as such, has been included in many analyses of community benefits. Research has shown it comprises the largest category of such benefits, between 40 to 45 percent of total benefit spending.23

There are several problems with including this concept in the definition of community benefits. The biggest flaw is that the evidence shows that nonprofit hospitals do not differ from their for-profit counterparts with respect to Medicaid costs, and in half of states with both types of hospitals, nonprofits had lower Medicaid cost to expense ratios relative to for-profits.24

Also, there are a number of ways that the federal government and state governments plus-up hospital payments for those that serve a high proportion of indigent patients. Federal Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are one type of targeted payment, with allocations to states totaling over $14 billion a year from 2020-2022.25 Moreover, there are various types of other supplemental Medicaid payments intended to lift hospital finances but not directly connected to service provision that have grown substantially over time. The fastest growing of these are “State Directed Payments,” which allow states to lift hospital payments up to the levels of commercial insurance and which have likely eliminated any 'Medicaid shortfall" in at least some states.26

It is also true that for Medicaid, reimbursement levels are determined predominantly by state governments and are not linked to specific nonprofit hospital decision-making based on community needs. There are other categories of community benefits reported on the 990 that are similarly problematic in that they aren’t linked to hospital decisions about community needs. For example, health professional education expenses may be useful for society at large but may not aid the local community or address the health-related needs of people served by an individual nonprofit hospital.

The Cost of the Nonprofit Hospital Tax Benefit

The cost to the federal government from allowing hospitals to claim nonprofit status, in the form of lost tax revenue, is substantial. There is an abundance of evidence that the tax benefits to those hospitals exceed tangible community benefits that are supposed to be tied to nonprofit status.

By our rough estimate, the existence of nonprofit hospital status will cost the federal government $260 billion over a decade in lost revenue. This includes forgone corporate tax revenue, the benefit associated with being able to issue tax-exempt bonds, and lost individual income tax revenue related to the deductible charitable contributions from donors.

Importantly, this estimate is rough and comes with a high degree of uncertainty. Challenges arise from the limited availability of comprehensive data on hospital income, tax rates, and the scope of revenue implications, spanning federal, state, and local levels. Our estimate is derived from two calculations by KFF of the cost of the federal tax breaks in 2020. They estimated the cost at $14.4 billion using their own methodology and $18 billion using the methodology of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.27

Notably, our estimate is based on current tax rates and deducted charitable contributions and thus effectively assumes full extension of the expiring parts of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The cost would likely be higher under current law and could differ in other ways depending on the tax reforms and modifications enacted as part of a possible 2025 tax bill.

Conclusion

Given its large cost and questionable value, policymakers should work to reform or repeal the tax advantages for nonprofit hospitals and should also improve the regulatory regime to ensure transparency, accountability, and provision of community benefits.

Short of a full or partial repeal, several potential solutions exist to improve the value and combat the inefficiency of the tax benefits (we dive more deeply into them in the appendix). It’s worth noting that states have also tried to address these issues by implementing general community benefit requirements, minimum standards linked to property tax amounts, and/or income thresholds for free or reduced-cost care.28

Increased transparency through improved hospital reporting and publication of data would enhance accountability and enable stakeholders to better assess hospitals' performance in delivering community benefits. The next step would be to define the concept of community benefit more explicitly, thereby establishing a standardized framework for evaluating hospitals' contributions to their communities. Additionally, setting minimum acceptable levels of community benefit spending could establish benchmarks to ensure hospitals are meeting their obligations effectively. Moreover, expanding enforcement efforts by subjecting hospitals to greater scrutiny and imposing real penalties for violations could incentivize compliance with community benefit requirements. Ultimately, if the system remains unworkable and there are other, more efficient health care system investments, or revenue is needed, the option of eliminating the tax deduction altogether could be considered.

Appendix: Possible Reforms

1. Refine Reporting and Require Greater Transparency

Form 990 Schedule H is intended to serve as the vehicle for the IRS and other stakeholders to learn where hospitals are steering their community benefit resources. For there to be true transparency, the IRS needs to revamp Schedule H to require hospitals to give much more detail on the nature and quantity of their community benefit spending. Furthermore, the IRS should produce annual reports based on the aggregated data and make the complete dataset available to qualified independent researchers.

One important change would be for Congress to mandate that reporting of hospital community benefit programming and outlays be done at the facility level rather than at the parent organization level. Although GAO recommended this change in 2020, the IRS dismissed it as “such reporting would impose [a] greater burden on tax-exempt hospitals and IRS with no tax administration benefit.”29

However, “tax administration benefit” is not the true goal. Taxpayers need more visibility as to the real beneficiaries of hospitals’ contributions. For example, in a multi-hospital system operating a central teaching hospital and several community general hospitals, facility-level reporting would reveal if a disproportionate amount of the dollars was going toward medical education, which as discussed before, isn’t necessarily benefiting the local community.

2. Issue Rules on Valuing Tax Exemptions

To further establish taxpayer visibility, the IRS could establish guidelines for quantifying the dollar value of federal tax exemptions for nonprofit hospitals. These guidelines are essential for resolving inconsistencies, particularly in assessing the value of uncompensated care, which currently exist between the IRS instructions for completing Form 990 Schedule H, Medicare's cost reporting requirements, and the generally accepted accounting principles of the Financial Accounting Standards Board.30 With clear guidelines in place for determining the net income or profit of nonprofit hospitals, the IRS and other stakeholders could eliminate debates surrounding the worth of the tax exemption.

3. Define Community Benefit More Plainly

Having a clear definition of acceptable forms of community benefit is crucial to ensure that hospitals, the government, and independent monitors can understand hospital expectations and measure performance. In its 2020 report, GAO recommended that Congress revise the tax code to better specify what services and activities qualify as community benefit.31

Certain questionable categories currently included in the IRS's list of acceptable expenditures, such as the Medicaid shortfall and medical education costs, should be reconsidered. Alternatively, any funding hospitals receive to offset these costs should be deducted from their calculations of community benefit expenditures.

At the same time, the rules need to be modernized to take account of new and different ways that hospitals may support their communities including newer programs that address “social determinants of health” including housing and nutrition programs. Further value would come from requiring hospitals to focus their community benefit spending on needs identified in their ACA-mandated community health needs assessments.

4. Set Minimum Levels of Community Benefit Spending

After defining what constitutes community benefit and understanding the extent of federal tax exemption for nonprofit hospitals, determining the baseline level of community benefit spending should theoretically be straightforward. However, there will always be some ambiguity and the potential for manipulation by motivated parties. Therefore, to ensure accountability, Congress could establish a minimum requirement for community benefit spending.32

Oregon offers one of the few models for such a system.33 The methodology, devised by the state with input from hospitals and others, considers multiple factors to recognize the different circumstances of each hospital: historic and current community benefit spending by the hospital and its affiliated clinics; demographics of the population served; spending on social determinants of health by the hospital and affiliated clinics; identified community needs; the hospital’s need to expand the health care workforce; the financial position of the hospital and affiliated clinics; and any taxes paid to federal, state, or local authorities.

5. Expand Enforcement

Per the ACA’s requirements, the IRS reviews every nonprofit hospital’s community benefits at least every three years. Whether the IRS reviewers are probing deeply enough or making enough referrals of potentially noncompliant hospitals is less certain. Thus, Congress could direct the IRS to strengthen enforcement and provide the agency more enforcement tools. First, the IRS should widen the focus of its community benefit activity reviews to fully encompass hospitals’ financial assistance and billing and collections practices. The aggressive efforts of some hospitals when it comes to pursuing patients for unpaid bills need policing as much as do hospitals community benefit spending, if not more so.

Second, the IRS needs a wider array of sanctions to apply to noncompliant hospitals. Today, if the IRS determines that a hospital is in violation, its available sanctions are severe: either requiring the hospital to pay federal taxes on all its net income for the year in question or revoking the hospital's tax exemption entirely. The IRS should be empowered to impose intermediate sanctions – such as fines of varying degrees – based on the nature and scale of a hospital's infractions. Freed from the burden of proving a massive and incontrovertible violation, the agency would have a stronger incentive to identify and address noncompliance. Additionally, hospitals facing intermediate sanctions might be incentivized to improve their performance rather than resorting to challenging extreme penalties.

1 Bai et al, “Do Nonprofit Hospitals Deserve Their Tax Exemption?” New England Journal of Medicine, 2023;389(3):196-197, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2303245.

2 American Hospital Association (AHA), "Fast Facts on US Hospitals, 2024,” https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

3 KFF (March 2023), “The Estimated Value of Tax Exemption for Nonprofit Hospitals Was About $28 Billion in 2020” [Issue Brief], https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/the-estimated-value-of-tax-exemption-for-nonprofit-hospitals-was-about-28-billion-in-2020/.

4 The Hilltop Institute (March 2013), “Hospital Community Benefits After the ACA: The State Law Landscape” [Issue Brief], https://www.hilltopinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/Hospit….

5 National Health Law Program (July 2011), “Nonprofit Hospitals and Community Benefit” [Issue Brief], https://healthjusticenetwork.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/nhelp_community_benefit.pdf.

6 Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Rev. Rul. 69-545, 1969-2 C.B. 117, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/rr69-545.pdf

7 Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Rev. Rul. 69-545, 1969-2 C.B. 117, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/rr69-545.pdf.

8 Specifically, the ACA “requires additional transparency from nonprofit hospitals and prohibits some of the more egregious charging and collection activities.” National Health Law Program, “Community Benefit” Issue Brief (July 2011).

9 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Tax Administration: Opportunities Exist to Improve Oversight of Hospitals' Tax-Exempt Status,” September 2020, Report no. GAO 20-697, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-679.

10 Id.

11 Bai, “Do Nonprofit Hospitals Deserve Their Tax Exemption?”

12 Only “Medicaid shortfall” is a larger community benefit expense, but as argued later in the brief, it should not be considered a community benefit.

13 Bai et al, “Analysis Suggests Government And Nonprofit Hospitals’ Charity Care Is Not Aligned With Their Favorable Tax Treatment,” Health Affairs, 2021;40(4):629-636, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01627.

14 The 4.3 percent number for the value of the tax exemption relative to operating expenses, used by Hopkins and KFF, comes from: Zare et al, “Comparing the value of community benefit and Tax-Exemption in non-profit hospitals,” Health Services Research, 2022;57(2):270-284, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13668.

15 KFF (November 2022), “Hospital Charity Care: How It Works and Why It Matters” [Issue Brief], https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/hospital-charity-care-how-it-works-and-why-it-matters/.

16 Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Katie Thomas, “They Were Entitled to Free Care. Hospitals Hounded Them to Pay,” NY Times, September 24, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/24/business/nonprofit-hospitals-poor-patients.html. Another health system gaining notoriety for its community benefit approach is Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, a 6-hospital system based in Memphis, TN, that launched 8,300 lawsuits to collect money owed by patients, some of whom were its own employees. “Its handling of poor patients begins with a financial assistance policy that … all but ignores patients with any form of health insurance, no matter their out-of-pocket costs. If they are unable to afford their bills, patients then face what experts say is rare: A licensed collection agency owned by the hospital.” Wendi C. Thomas, “The Nonprofit Hospital That Makes Millions, Owns a Collection Agency and Relentlessly Sues the Poor,” ProPublica, June 27, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/methodist-le-bonheur-healthcare-sues-poor-medical-debt.

17 Hashim et al, “Characteristics of US hospitals using extraordinary collections actions against patients for unpaid medical bills: a cross-sectional study,” BMJ Open 2022;12:e06050. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/7/e060501.

18 Lown Institute Hospitals Index, “Fair Share Spending: Are hospitals giving back as much as they take?” 2024, https://lownhospitalsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/lown-institute-fair-share-policy-brief-20240321.pdf; see also Lown Institute, “Hospital Community Benefit Spending: Improving transparency and accountability around standards for tax-exempt hospitals” [Policy Brief], https://lownhospitalsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/lown-institute-fair-share-policy-brief-20240321.pdf.

19 Bai, “Hospitals’ Charity Care Is Not Aligned With Their Favorable Tax Treatment”; Zare “Comparing the value of community benefit and Tax-Exemption in non-profit hospitals.”

20 U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, “Grassley Releases Non-profit Hospital Responses, Expresses Concern Over Shortfalls in Charity Care, Community Benefit” [Memorandum], September 12, 2006, https://www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/grassley-releases-non-profit-hospital-responses-expresses-concern-over-shortfalls-in-charity-care-community-benefit

21 Letter from Senators Warren, Warnock, Cassidy and Grassley to Commissioners Werfel and Killen, August 7, 2023, https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Letters%20on%20Nonprofit%20Hospitals.pdf.

22 It’s worth pointing out that the AHA includes an accounting of the “Medicare shortfall” in their total for community benefit spending as well – a position even more difficult to take seriously than the Medicaid shortfall. AHA, “Tax-exempt Hospitals Provided Nearly $130 Billion in Total Benefits to their Communities,” October 2023, https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2023-10-09-results-2020-tax-exempt-hospitals-schedule-h-community-benefit-reports.

23 Bai et al, “Evaluation of Unreimbursed Medicaid Costs Among Nonprofit and For-Profit US Hospitals,” JAMA Network Open, 2022;5(2):e2148232, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2789009; Zare et al, “Charity Care and Community Benefit in Non-Profit Hospitals: Definition and Requirements,” INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 2021;58, https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211028180.

24 Bai, “Evaluation of Unreimbursed Medicaid Costs.”

25 Congressional Research Service, “Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments,” November 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42865.

26 Kempski, Ann and Gee Bai, "Medicaid Financing Requires Reform: The North Carolina Case Study," Health Affairs Forefront, March 28, 2024, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/medicaid-financing-requires-reform-north-carolina-case-study.

27 Our estimate is the midpoint between $212 billion to $307 billion of this range with different plausible growth paths. KFF, “Estimated Value of Tax Exemption” Issue Brief (March 2023); Gerard Anderson, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, phone interview, March 20, 2024. KFF methodology determined taxable income from hospital-level data while Hopkins methodology employs tax-filing data. In an estimate of the tax break cost in 2019, the AHA put forgone revenue at $12.4 billion, in line with the KFF and JHU estimates. AHA, “New EY Analysis: Tax-Exempt Hospitals’ Community Benefits Nine Times Greater Than Value of Federal Tax Exemption” [Press Release], June 6, 2022, https://www.aha.org/press-releases/2022-06-06-new-ey-analysis-tax-exempt-hospitals-community-benefits-nine-times.

28 See Hilltop Institute, “Community Benefits After the ACA” Issue Brief (March 2013). Six states (IL, NV, OR, PA, TX, UT) have enacted minimum community benefit requirements, each with varying specifications. For instance, Illinois and Utah mandate that nonprofit hospitals contribute amounts equivalent to the property taxes they would owe if not exempted, while Pennsylvania and Texas require hospitals to meet specific standards. Eleven states (CA, CO, IL, ME, MD, NH, NY, OK, RI, TX, WA) have defined income thresholds, usually as a percentage of the federal poverty level, to determine eligibility for free or reduced-cost care.

29 GAO-20-697, Recommendations for Executive Action, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-679.

30 See e.g., “Evaluating the Methods for Calculating and Reporting Uncompensated Care,” PYA, March 11, 2021, https://www.pyapc.com/insights/evaluating-the-methods-for-calculating-and-reporting-uncompensated-care/.

31 See GAO-20-697, Recommendations for Executive Action.

32 In 1993, Texas passed a law, since amended, mandating that nonprofit hospitals spend a minimum of 4% of net patient revenue on charity care. An unintended consequence was that hospitals already spending more than that percentage reduced their charity care spending. Kennedy et al, “Do non-profit hospitals provide more charity care when faced with a mandatory minimum standard? Evidence from Texas,” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 2010;29(3):242-258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2009.10.010.

33 Oregon Health Authority, “HB 3076 Implementation Report: Status of the new hospital community benefit program, expanded financial assistance, and new medical debt protections,” December 2022, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/HospitalReporting/HB-3076-Comm-Benefit-Leg-Report.pdf

What's Next

-

Image

-

Image

-

Image