Maya MacGuineas and Stuart Butler Publish Joint Paper Over Long-Term Budgeting

CRFB president Maya MacGuineas and Brookings Institution senior fellow Stuart Butler published a paper last week outlining a plan to create a long-term budget. This plan updates MacGuineas, Butler, and others’ work on the Taking Back Our Fiscal Future project in 2008 by setting that framework into action, and it addresses many of the topics MacGuineas and Butler proposed in their testimonies to the House Budget Committee in 2016. MacGuineas and Butler developed this new long-term budget proposal in order to “create a structure that allows for the important goal of creating programs that are based on credible longer-term commitments while ensuring that they do not squeeze out other budgetary priorities.”

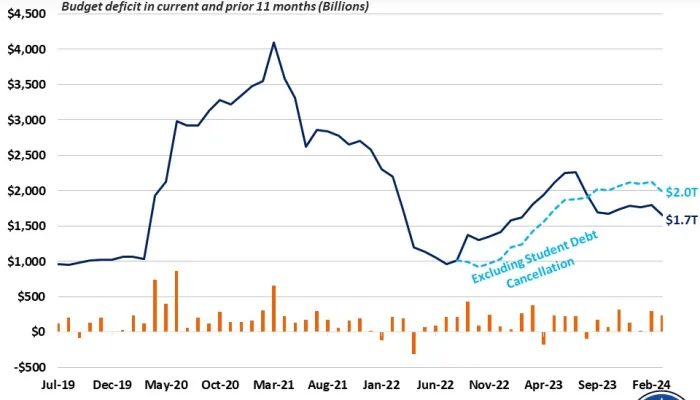

The CBO projects that the debt will grow from 75 percent of GDP today to exceed the size of the economy by 2033 and reach 141 percent of GDP by 2046. Within the next two decades, the Medicare Part A and Social Security Trust Funds will have just reached or be nearing insolvency.

MacGuineas and Butler’s proposal tackles these long-term problems head-on by using two separate elements to create and enforce fiscal targets for the long-term budget. The first element includes a policy goal that requires Congress to enact a 25-year spending and funding plan for major entitlements (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc.). The funding portion of this plan would include taxes, other revenues, or specified savings from other programs. Once adopted, this plan would serve as the default for mandatory spending unless Congress decides to make explicit changes during a formal review that would occur every four years after a presidential election.

The second element is referred to as an “‘inside-outside’ approach.” In the “inside” portion of this approach, Congress would create a bicameral, bipartisan super-committee that could also make adjustments to the long-term budget that could take effect if it is passed by certain procedures. In the “outside” portion of this approach, Congress and the President would appoint a commission that is tasked with regularly making spending and revenue adjustments to ensure the long-term budget will hit its targets. The outside prong of this proposal protects this long-term budget from being subjected to partisan debates and encourages future Congresses to remain committed to this budget by placing its regular adjustments outside of Congressional control. The inside prong of this proposal allows for Congress to make adjustments if necessary.

MacGuineas has previously published a paper on the problem of the “lame-duck” presidency, or the idea that pre-committed growth in autopilot spending programs will crowd out President Trump’s policy priorities. MacGuineas and Butler’s work on this long-term budget proposal addresses this lame-duck problem head-on by creating a process for Congress that introduces scrutiny into entitlement spending.

MacGuineas and Butler conclude:

Future beneficiaries need the security that a long-term budget would bring, but they also need the assurance that the goals of these programs and the resources for them allow other goals to be achieved and the economy to remain strong. Accomplishing that requires long-term budgets and a procedure to keep to a plan unless there is an explicit decision to change it.

With the national debt reaching its highest share of the economy since President Truman’s tenure, this proposal holds much promise. While process cannot be a substitute for the political will necessary to make difficult policy choices, the framework for decision-making matters and can help provide the space for creating fiscally-responsible solutions to address our unsustainable long-term debt.

Click here to read MacGuineas and Butler’s paper.

To read more about bringing the long-term into our budget process, read our paper “Improving Focus on the Long Term.”

To read more about budget process reform, please visit our Better Budget Process Initiative.