How Medicare Part D's Low-Income Subsidy Could Work Better

During the recent slowdown in Medicare spending, the prescription drug portion of the program, Part D, has been the lead actor in the story. The unexpectedly slow growth of prescription drug costs has made Part D cost much less than anticipated. But a new CBO working paper by Andrew Stocking, James Baumgardner, Melinda Buntin, and Anna Cook shows how Part D costs could be further controlled by improving the design of Medicare Part D's Low-Income Subsidy (LIS).

For background, the LIS helps people below 150 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) afford the costs associated with Part D prescription drug plans. For those with income below 135 percent of the FPL, the LIS covers all premiums as long as the beneficiary chooses a plan that costs below the region's benchmark (ranging between about $20 and $40 per month in 2014), pays the entire deductible, and leaves minimal co-pays for drugs (for those between 135 and 150 percent of the FPL, the LIS covers a portion of each of these items). If LIS beneficiaries choose a plan with a premium above the benchmark, they pay the difference. If a plan that costs below the benchmark in one year moves above the benchmark in the next, Medicare automatically re-assigns beneficiaries to a plan below the benchmark unless they actively choose to stay with the plan or had proactively chosen their Part D plan originally.

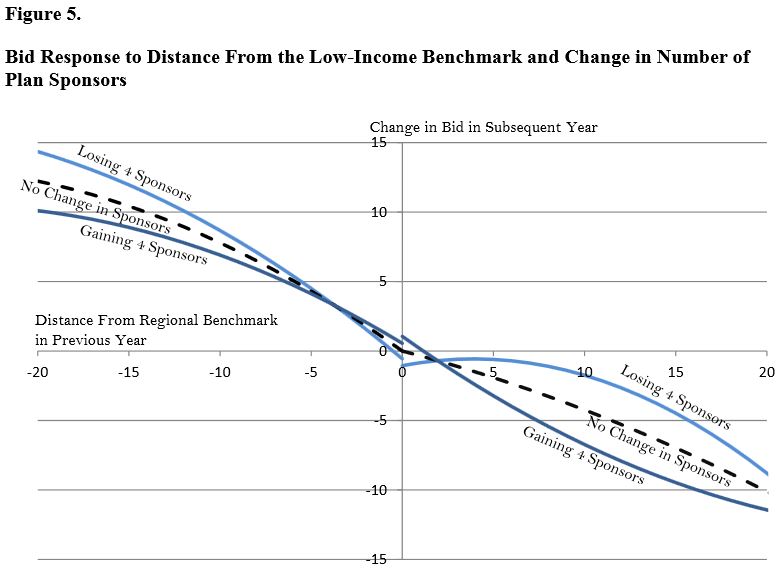

The working paper looks at the difference in responses to competitive pressures from LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries and plans. Not surprisingly, LIS beneficiaries tend to be in less expensive plans because of the automatic assignment to plans at or below the benchmark; 87 percent of LIS beneficiaries are in a plan that is within 50 percent of the least expensive plan in the region, compared to two-thirds of non-LIS beneficiaries. But the authors note that plans catering to LIS beneficiaries tend to increase their premiums in the next year if they fall below the benchmark, since they have little incentive to have lower premiums once they are below; plans are estimated to raise monthly premiums by between $6.90 and $9.70 if they fell $10 below the benchmark in the previous year. Furthermore, the addition of a new plan sponsor into a region is estimated to lower plan bids by 0.5-0.8% for non-LIS plans, but only 0-0.2% for LIS plans.

The less responsive nature of LIS plans to competition is part of the design of LIS in shielding beneficiaries from costs, but it is also due to the binary distinction of being either above or below the benchmark. The authors suggest a number of ways to create competition among the below-benchmark plans rather than having them try to play The Price is Right -- get closest to the benchmark without going over.

-

- The first strategy would narrow the re-assignment method from just any plan below the benchmark to a select number of the lowest-cost plans. This would directly lower costs by having re-assigned beneficiaries in lower-cost plans, but it would also lower the benchmark, which is determined by the enrollment-weighted average plan premium, and give an incentive for below-benchmark plans to compete. There are minor trade-offs with this plan, though, in restricting plan choice for LIS beneficiaries. This idea is a variant on the "smart re-assignment" policy we discussed earlier this year that would re-assign beneficiaries to the plan that would have minimized their drug costs the previous year.

- The second strategy would allow below-benchmark plans to opt out of being re-assigned LIS beneficiaries. This would reduce the disincentive for plans to go below the benchmark if they did not want to cover that group. Of course, the drawback would be a potential decline in plan choices for LIS.

- The third strategy would encourage beneficiaries to pick lower-cost plans by giving them a cash award based on how much below the benchmark their plan's premium is. The concerns with this policy are similar to the first, but also that the award might more provide a windfall for those already in lower-cost plans rather than a subsidy for those switching plans. Lawmakers would have to design this policy carefully to make sure it functions as intended.

Part D has been a significant source of the federal health care spending slowdown, but that doesn't mean it can't be improved to be more efficient. There are plenty of ideas to do that, and the CBO study contributes understanding of ways policymakers can make the Part D low-income subsidy work better.