The Basics of the Budget Conference Agreement

Yesterday, we discussed The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of the Budget Conference, where we showed how the budget conference agreement was a mixed bag when it came to important procedural and policy issues. This blog takes a step back to look at the overall savings the budget intends to produce and how it compares to the original House and Senate budgets.

Like the House budget, the conference agreement proposes bringing the budget into balance starting in 2024. Compared to a baseline that includes the physician payment law (HR 2), a drawdown of war spending, and the removal of one-time emergency spending, the conference agreement assumes savings of $5.3 trillion over ten years, splitting the difference between the House and Senate, which had savings of $5.6 and $5.1 trillion, respectively. The $5.3 trillion total consists of $4.4 trillion of policy savings, $718 billion of interest savings, and $124 billion from the fiscal dividend that incorporates the economic effects of deficit reduction.

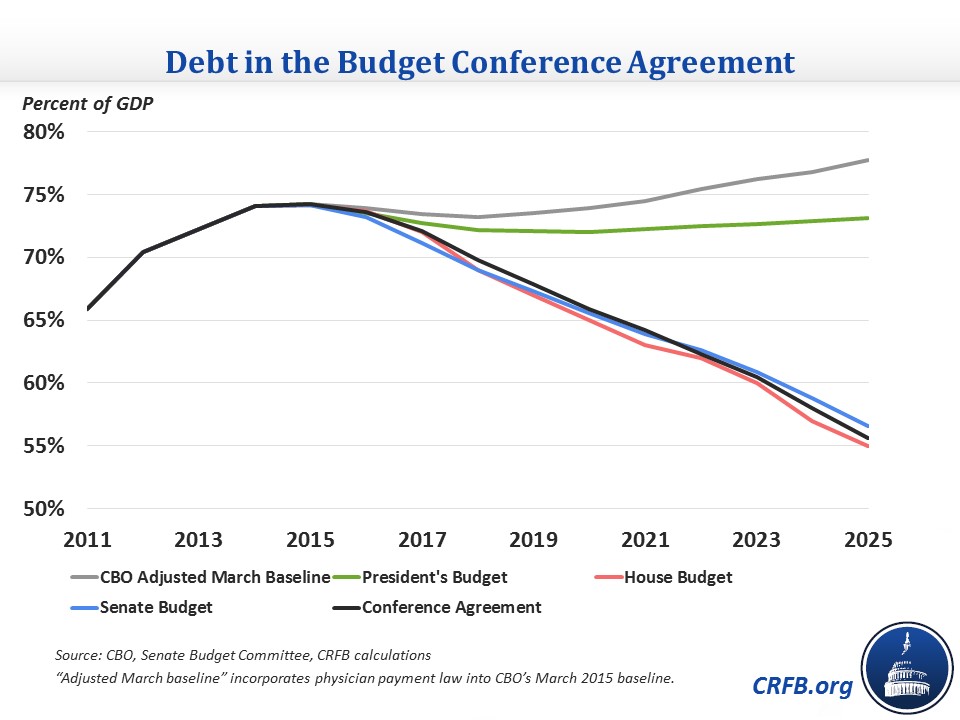

These savings would put debt on a clear downward path from 74 percent of GDP this year to 56 percent by 2025, again splitting the difference between the House and Senate. This path would be a clear improvement on current law and well below where the President's budget is. However, the President's budget is much more specific, listing individual policies to claim deficit reduction, while the budget resolution leaves many of its savings unspecified; indeed, the Senate committee allocations put nearly $5 trillion of savings in the "unallocated" category, so no committee is responsible for achieving them.

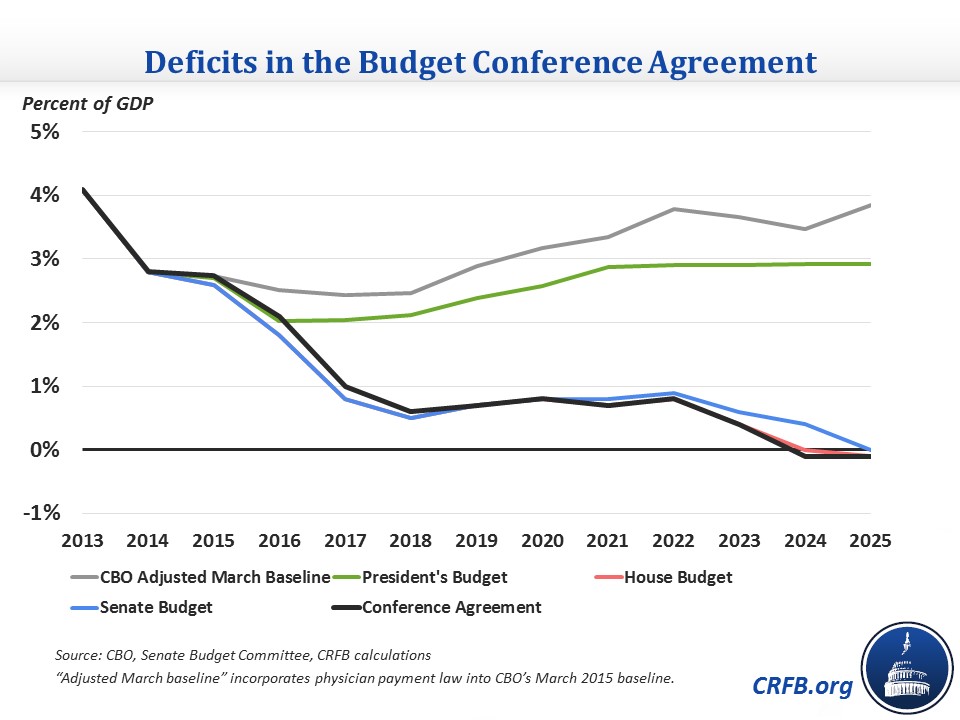

As mentioned above, the conference agreement intends to balance the budget by 2024. It reduces deficits from the current 3 percent of GDP to below 1 percent by 2018 and then to a small surplus in 2024 and 2025. The budget balances with spending and revenue at just over 18 percent of GDP.

Like both original budgets, the conference agreement gets most of its assumed savings from health care spending, and in particular from repealing the gross spending in the Affordable Care Act. The budget adopts the Senate's level of gross Medicare savings, although the passage of the physician payment law means that total Medicare spending is $147 billion higher than the Senate budget. The budget includes about $50 billion of defense increases for 2022-2025 (much less than the House but more than the Senate) after sticking with the current caps through 2021, $600 billion of non-defense discretionary and highway spending cuts (between the House and Senate), and $170 billion of war spending increases relative to the President's request through 2021 to backfill the regular defense budget. Finally, the budget includes nearly $1.4 trillion of other mandatory spending, a greater amount than was in either budget. These savings are mostly unspecified but nearly half of the cuts would come from the income security function, which includes non-health safety net programs and federal retirement spending.

| Policy Changes in the FY 2016 Conference Agreement | |

| 2016-2025 Savings | |

| Affordable Care Act and Medicaid | $2,273 billion |

| Medicare (net)* | $431 billion |

| Social Security | $4 billion |

| Other Mandatory | $1,357 billion |

| Discretionary and Highway | $381 billion |

| Revenue | $0 billion |

| Interest | $718 billion |

| Subtotal, Policy Savings Against Conference Baseline | $5,165 billion |

| Fiscal Dividend | $124 billion |

| Subtotal, Claimed Savings with Fiscal Dividend | $5,289 billion |

| Baseline Adjustments^ | $488 billion |

| Total, Claimed Savings Against CBO March Baseline | $5,777 billion |

Source: House Budget Committee

*Excludes $147 billion of higher spending from physician payment law, which is already in the baseline

^Includes war spending drawdown, removal of current emergency funding from future years, and physician payment law

Overall, the budget calls for significant savings, but it is questionable whether or not lawmakers intend to actually achieve these savings. As we noted yesterday, the budget has large amounts of unspecified and possibly unrealistic savings, includes reconciliation instructions only for repealing the Affordable Care Act, and uses revenue levels that are inconsistent with what at least the House has called for. In fact, the Senate Committee allocations in the conference report that are used to enforce the budget resolution assume spending continues at current law levels for all committees, with nearly $5 trillion of policy and interest savings going to the “unassigned” category. Ultimately, a budget resolution only provides a framework for lawmakers; whether they follow through and actually implement and enforce it is another matter altogether.